2.4K

INDIANAPOLIS — Jerry Michael “Mike” Bayles was born on Oct. 18, 1959, to Gerald “Jerry” Bayles and Fannie Lucille Bayles, who married in 1952. The family resided at 3028 W. Jackson St. on the city’s west side.

Jerry, 10, preferred to be called Mike. With his red hair, he resembled Opie from the “Andy Griffith Show.” Mike was a fifth-grader at Nathanial Hawthorne School 50, now Providence Cristo Rey High School.

By the fall of 1970, Mike’s parents had fallen on hard times. Bayles, a truck driver, was unemployed due to a strike. Mrs. Bayles worked in a local restaurant, bringing in the family’s sole income.

Mike’s older brother, Gordon “Bud” Bayles, 15, got a job delivering the Indianapolis Star newspaper during the summer. Mike tagged along every morning and a few times a week after school started; he knew the route quite well.

Mike also did odd jobs for nearby businesses.

Mrs. Harold Nichols, an employee at a Burger Chef restaurant, told the Indianapolis Star in 1970 that Mike was a “hard worker more interested in working than playing like most kids,” and he “was all the time working around trying to make a quarter. He saved his money and gave it to his mom and dad.”

For being only 10 years old, Mike was a responsible and downright good kid. So when he offered to cover Bud’s route one fall morning when Bud was not feeling well, no one thought anything of it. Unfortunately, it would be the first and last time Mike went alone.

Early Saturday morning, Oct. 3, 1970, Mike hopped out of bed, ready to take on the day.

“It’s Saturday, no school,” Mike told Bud. “You can sleep because I know how to deliver the papers on your route.”

It was a typical October morning with temperatures in the mid-50s. Mike wore black jeans, a yellow shirt with “pinkish” stripes, black tennis shoes, and a blue fingertip jacket.

Mike left home on a neighbor’s bicycle around 4:30 a.m. and rode to the newspaper’s district circulation office, located at 2502 W. Washington St. He collected 48 newspapers before riding to Harris Avenue and Washington Street to begin his route.

There are a few time discrepancies on what happened next.

A story published in the Indianapolis Star on Oct. 4, 1970, reported two female witnesses heard a scream.

The first unidentified woman who lived in a house on Harris Avenue and Washington Street told Bud during a morning search that she heard a scream shortly after 5 a.m., but all she saw when she looked out her bathroom window was the headlights of a departing car.

Mrs. Thomas P. Baker, 40, lived a block east of Harris Avenue on South Warmen Avenue. An alley behind her house connected Warman and Harris Avenues. Baker also heard a scream, but it was between 4:45 and 5 a.m. But her statement slightly contradicted the unidentified woman’s account. Regardless, police believed both women listened to the same scream.

In a story in the Indianapolis News published on Jan. 18, 1979, the newspaper reported that “a female neighbor heard the newspaper’s thump as Mike tossed it onto the front porch, followed by a scream shortly before 6 a.m.” It is unclear if the neighbor is one of the two female witnesses mentioned above, but if so, the 1979 piece might have been a typographical error.

William H. Johnson, 12 S. Harris Ave., opened his front door to get the morning paper and found Mike’s abandoned bicycle with the chain hanging loose from the sprocket, but no sign of the young boy.

Several subscribers called Mike’s parents, saying they had not yet received their newspapers.

At 6:30 a.m., Bud went to the start of the route and found Mike’s bicycle and 46 of the 48 newspapers delivered in front of Johnson’s home on Harris Avenue. Mike had folded none of the remaining papers.

Bud returned home to tell his parents, and his mother called the police to report Mike missing. Authorities suggested that the Bayles family continue looking for the boy in the immediate area before they would get involved.

After Bud finished the route, he accompanied his brothers, John, 12, James, 8, and their father, to search for Mike.

Meanwhile, at 8:55 a.m., a farmer, Marion Adkins III, aged 21 of Shirley, drove his tractor along West County Rd 550 S, then a gravel road, and found Mike’s body face up in 4-foot high weeds five miles north of Kingstown in Eastern Indiana. The location is roughly 40 miles from the Bayles residence.

The body was not visible from a car on the road. The description of the body matched the missing boy. The body was nude except for socks.

Officer Glen Cupp of the Knightstown Police Department arrived at the scene at 9:25 a.m. Mike’s body was still warm, and Cupp found drag marks from the boy’s heels 15 feet to the ditch from the road.

Authorities began a 2.5-mile search around the location.

At 1 p.m., the Bayles family listened to a radio broadcast revealing the discovery of a boy’s body. Mike’s father called the state police, and a state trooper came to the house to get a picture of Mike.

The trooper returned at 6 p.m., and an hour later, the Bayles officially identified the dead child as their son.

Bayles told the Indianapolis Star, “When I saw the red hair, I knew it was him.”

That same night, Bud, John, a family friend, and an Indianapolis Star reporter retraced Mike’s final steps and found what appeared to be a dried patch of blood about a foot from the curb in front of 12 South Harris Ave. where Mike disappeared. The patch was about 12 inches long and 3 inches wide. However, tests later revealed it was not blood.

Two autopsies were conducted on the body. The first one was “not complete enough,” said Captain Robert Gray, who headed the state police investigation at the time.

Henry County Coroner David L. Estell performed the first autopsy. While he determined the immediate cause of death as internal hemorrhaging from knife wounds, the autopsy “did not go far enough because the skull was not examined and a blood sample was not taken.” Gray pointed out that if police arrested a suspect, there would be no way to connect the suspect to the murder without a blood sample.

The crime occurred more than a decade before the use of DNA testing in criminal cases. By testing the blood, 1970 officials would only be able to learn the blood type.

The autopsy revealed Mike had been stabbed nearly 10 times, possibly with a long-bladed knife, in the abdomen and back. Mike’s body bore several bruises on the neck and right arm.

Estell estimated the time of death at 6:30 a.m. and said there was no evidence of sexual molestation. Marion County coroner Dennis J. Nicholas conducted the second autopsy. However, he only revealed Mike’s hand had a few slight bruises that could have resulted from a fall before the murder or a struggle with the killer.

The investigation into Mike’s murder officially started at 4:30 p.m. on Sun. Oct. 4, 1970, according to newspaper articles at the time. Police found no relevant evidence at the body location and not “enough blood for it to be feasible that the murder happened there,” said Sgt. Martin Werling, State Police Detective.

For unknown reasons, the police never confiscated the bicycle to check for fingerprints. All the neighborhood children used the same bike, so there would have been multiple fingerprints on it.

Police never found Mike’s clothing or the murder weapon. Mike was believed to have carried $21 in newspaper collections in his pocket. His father and the police initially thought the motive was a robbery because there was no sign of sexual assault. But the amount seemed too low to kill a child over.

Police also discovered a two to three inches long string of red thread near the abandoned newspapers at the abduction site. They found a similar thread where Adkins found Mike’s body. They had the strings tested, but the results are unknown.

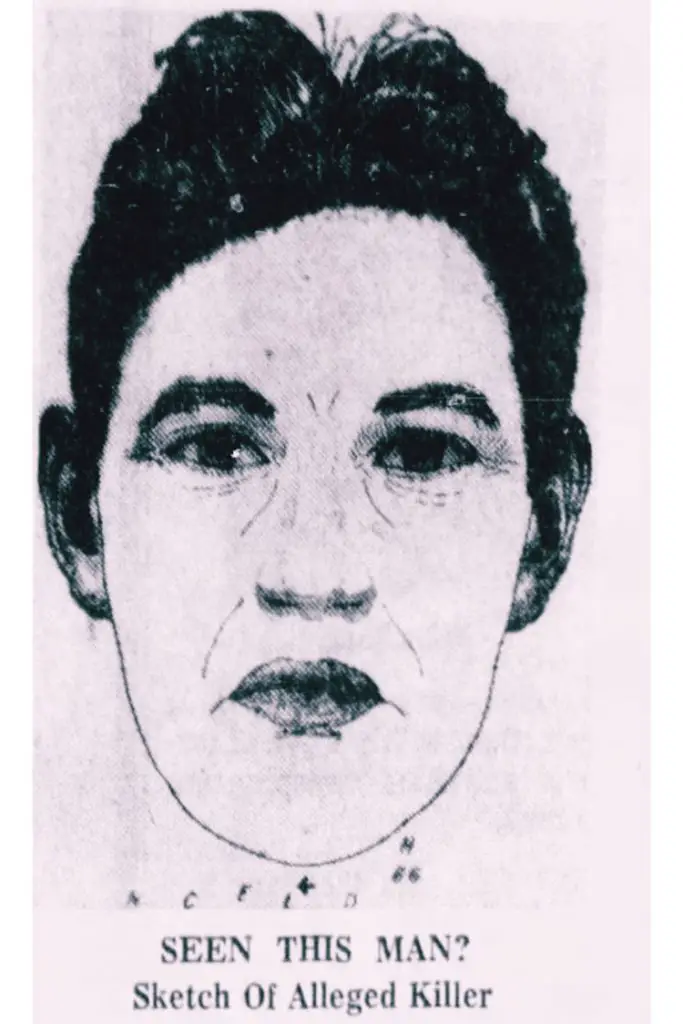

Paul Thomas McDougall, 34, lived in the 500 block of South Harris Avenue and was a manager at Star Service and Petroleum Station at 502 W.16th St. He claimed he was driving to work between 5 a.m. and 5:30 a.m. on Oct. 3 when he saw a vehicle parked at an angle in the street, blocking the road. McDougall then saw a man dragging a boy at knifepoint to a car where a second man was waiting. The man with Mike wore a dark work jacket.

McDougall stopped his car and heard the boy scream. He started to get out of his vehicle to complain about the parking. He said the boy did not speak while McDougall talked to the older man, and he did not question the boy.

The kidnapper was in his 20s, wearing a dark work jacket and dark trousers, and drove a 1959 or 1960 Plymouth or Chrysler car with fins on the rear fenders. The vehicle was light green or blue and dusty. Some reports stated the car was a 1950s Dodge or Rambler.

William Ott runs a website dedicated to Mike’s case. He reports that McDougall called the police on Sunday, Oct. 4, but newspapers stated it was the next day. After McDougall hollered at the man, Ott wrote that he “told the man it was a terrible way to treat a child. Mr. McDougall stalled and pretending (sic) to lite (sic) cigarette in order to get the license plate. The plate was dust cover (sic) and had the county number for Marion County prefix of 49 P, E or F and a combination of 5 and 8.”

Some questioned McDougall’s story, saying he would not have used a knife to drag the child back home if the boy was the man’s son.

Investigators created a composite sketch of the man based on McDougall’s account.

Two other men, including the male witness, were given polygraph tests. Investigators cleared all men of involvement.

Eugene C. Pulliam, then-publisher of the Indianapolis Star and the Indianapolis News, donated $5,000 for a reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Mike’s killer. McDougall said he did not want the reward money, and if the killer was caught and convicted, he wanted the money given to the Bayles.

Gray came up with three possible routes the killer might have taken from the Johnson residence to the location of Mike’s body.

No. 1 – East on Washington Street to Interstate 465, then north on I-465 to Interstate 70, then on I-70 to an interchange just north of Knightstown, then north on State Road 109.

No. 2 – East on Washington Street to Knightstown then to north on State Road 109.

No. 3 – West on Washington Street to I-465, then around the south side of Indianapolis on the interstate to Washington Street, then east to Knightstown, then north to State Road 109.

Indianapolis Star, Oct. 18, 1970

Gray believed Route No. 1 was the killer’s most likely route to dispose of Mike’s body. He appealed for anyone who traveled any of the three routes the morning of Oct. 3, 1970, to come forward with any relevant information about the abduction and murder.

Shortly after the murder, a sobbing woman called Mike’s parents twice. She spoke with Mike’s father on Oct. 5, reaching him at the Farley Funeral Home.

The woman told Bayles, “I can’t give you my name Mr. Bayles, but I want to tell you, I know the man that saw your boy murdered and I’d like to talk to you.”

Police acknowledged the call might have been a hoax, and nothing more was reported on it.

She went on to say that she did not want to speak with detectives and that she was afraid for her life.

The following day at 8:30, she spoke with Mrs. Bayles in a call to the Bayles home, despite the family phone number listed in someone else’s name in the telephone directory. This led police to believe she knew the Bayles family.

The crying woman told Mike’s mother, “I’m scared to death. I need to talk to someone.”

Mrs. Bayles asked the woman what was wrong, and the woman replied, “The man who killed your boy is in the house at ….”

She gave an address and a first name and added, “This man did not kill your boy, but he saw it happen.”

The Bayles gave the police the address, and they went there, but the man had left. He had lived there until Oct. 5, but the woman never lived at the residence. She said the man was also afraid for his life and would not come forward.

In a separate phone call shortly after midnight on Oct. 17, a man with a “coarse” voice told Bud that his father should meet him at Monument Circle.

The caller said, “I killed Mike. I’m afraid I’m going to kill somebody else. I love you all. I’ve got to talk to you. Meet me at Monument Circle in 15-20 minutes.”

Investigators were convinced the killer was local.

A few days after the murder, Albert Garcia, 30, was arrested in Bowling Green, Kentucky, and brought to Indianapolis by detectives on warrants accusing him of sexually molesting two carriers for the Indianapolis Star in January 1970. He took and passed a polygraph, and investigators ruled him out as a suspect in the Bayles murder.

Ott reported that another female witness saw a man wearing a work jacket and a second man in the vehicle.

A Female Greenfield resident, driving north on State Road 9, south of Greenfield near the Park Cemetery witness (sic) a car parked on the east side of the road facing south, As she approached the car a man wearing dark blue pants and a work jacket crossed the road towards the car. The man walked towards the passage side of the car, fumbling with possible keys and mumbling. As she turned her head back towards the road a second man crossed the road and went to the driver’s side door of the parked car. He too was dressed in dark blue pants, and a work jacket. As she passed the car she notices that all the windows were up and a boy was sitting in the middle of the front seat, with a “wild frightful expression”.

An Oct. 24, 1970 piece in the Indianapolis Star said the woman wrote the tip in a letter to investigators.

Around Thanksgiving 1970, Indianapolis police arrested another suspect, Robert E. Schmidt, 47, after extradition from Phoenix. According to a Nov. 24, 1970 story in The Logansport Press, “Schmidt was committed in 1969 to Norman M. Beatty Hospital in Westville after he was indicted on charges of sexually molesting numerous Indianapolis boys. He was later transferred to Central Hospital where he was restricted to the hospital grounds but could have been unaccounted for roughly four hours between checks.”

Staff discovered he was missing during a routine bed check on the night of Oct. 10, a week after Mike’s body was found.

At a Marion County court hearing on Tuesday, Dec. 8, 1970, McDougall pointed at Schmidt and identified him as the man holding Mike at knifepoint on Oct. 3. Schmidt shook his head when McDougall made the identification.

A grand jury later had insufficient evidence against Schmidt to indict, and he was released.

On Sept. 14, 1971, Mike’s mother received an anonymous letter in the mail claiming the writer knew who killed her son. According to Ott, the author knew her first name even though newspapers never printed it.

From the Indianapolis Star, Monday, Oct. 4, 1971:

“Dear Mrs. Bayles,”

“Its all most been a year now.”

“I guess it seems longer to you.”

“You will never know who killed your boy, but I have something that will make you feel better. On the 3 day of Oct. you go to the alley by Harris Street where Mike left his bicycle and you will find a package. Come at 25 after 5 in the morning. You won’t see me but I will see you. Get the package and leave. Don’t be afraid I won’t hurt you. I did not kill Mike. But I know who did. If you knew you won’t believe it. I know your husband and all the boys. it won’t do any good to take this to the police. Some one else is writing this, not me. When you get the package go home before you open it please.”

Mrs. Bayles informed an Indianapolis Star reporter of the letter but not the police because she was afraid they would not let her go to the location. Her husband tried talking her out of it, but she went regardless. He then contacted the Indiana State Police about the letter.

The Star reporter “informed Capt. Raymond A. Koers, head of the Indianapolis Police Department’s homicide branch, and the two police agencies planned an extensive stakeout,” the Star reported.

At 1 a.m. on Oct. 3, 1971, Koers sat in an unmarked police car four blocks from the spot where Mrs. Bayles was supposed to pick up the package, scanning the neighborhood with binoculars.

Indianapolis Police Sgt. Robert J. Tirmenstein and State Police Sgt. Chester Inlow, assigned to the investigation after the murder, sat in a beat-up, unmarked panel truck surveilling the drop-off location.

Mrs. Bayles arose early on Oct. 3 and donned dark purple slacks, a flowery blouse, and white tennis shoes. She then left her home and slowly walked three blocks to where her son was kidnapped the year before, growing more terrified with each step.

Her husband followed but kept his distance from the location, often hiding behind trees to not be seen, keeping a close eye on his wife. However, no one ever arrived, and the package was not there when she showed. Mrs. Bayles thought the box would contain her son’s clothing that he wore when he disappeared. Her husband gently escorted the weeping mother back home.

By the end of the 1970s, the Bayles police file had topped at 5,000 pages, but police never solved the case.

Decades later, a woman contacted Ott through his website in 2015. She believed her father had killed Mike.

The woman was seven years old in 1970. The day after Mike’s murder, her mother instructed her to go into the bedroom and see if her father wanted a cup of coffee. She noticed bloody clothes and a knife on the bed.

Her father forced her to watch as he placed the clothes and knife in a paper bag and put them inside the wall. He told her he would do to her what he did to “that newspaper boy” if she ever told anyone. She was so frightened she never even told her mother.

She and her siblings were terrified because their father was known to snap and become abusive. According to WTHR, her father was the male witness in 1970 who claimed he witnessed the abduction — McDougall.

She said that her father had a temper and snapped when Mike’s bicycle ran out in front of his car.

Shortly after the murder, her father moved to California, and the family followed a while later. They lived in several locations before ultimately returning to Indiana.

She tried to tell the police and her teachers what she witnessed, but nobody believed her because she was a kid. Only when her father passed away did she have the courage to contact Ott.

Police stated they would look into the information and determine whether her father was a witness or killer. Nothing further has been reported, and the case remains officially unsolved.

To read more on Mike’s murder, please visit William Ott’s website. Anyone with information can call the police at (800) 527-4752.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

I’m pretty sure the woman who contacted Ott in 2014 is McDougall’s only daughter, Jo-Ann. The woman said her father had passed away; McDougall died in August 2013.

His story to police should have been a red flag, but instead of treating him like a person of interest or suspect, they considered him a witness, probably because he passed a polygraph. But we all know that guilty people can pass lie detector tests.

Anyway, the man supposedly was holding Mike at knifepoint, so why on earth would you believe the man’s son who was trying to run away? The man would not drag his son home at knifepoint. He likely would have grabbed his arm and forced him into the car but not pull out a freaking knife.

Here’s what I think happened. I believe that McDougall was driving to work on Oct. 3, 1970, when he spotted Mike alone on his bicycle near the Johnson residence and bumped the bike with the car to knock Mike off of it. Then, he kidnapped Mike at knifepoint. He took advantage of no one else around because it was early in the morning. No people, no witnesses.

McDougall took Mike to another location where he molested, or attempted, and killed him. The motive was not anger because why on earth would you kill a child for running out in front of your car? It was 5 a.m., so McDougall could have killed Mike right then and there if this was a road rage incident.

I also think Mike was responsible enough to look for cars as he rode his bicycle. Plus, he likely would have heard the car coming.

This was a moment-of-opportunity sexually motivated crime, regardless of what the autopsy showed. Maybe something went wrong, and the killer could not finish. But the boy was found nude, so if the crime was out of rage, why take off his clothes?

I believe that McDougall’s wife, Virginia is the weeping 1970 caller. She called the Bayles out of guilt and horror at what her husband had done and attempted to do the right thing. I also think she lied about the man being the witness and meant her husband, the killer. I’m not convinced that another person was involved.

It doesn’t make sense the caller would be sobbing over a witness to the crime., but it does make sense if her husband killed Mike, and she knew it. It also could have been another way of corroborating her husband’s statement that he saw another man in the vehicle.

I also think her husband forced her to make the phone calls to throw the police off and write the letter’s author instructing Mrs. Bayles to meet at the abduction site in 1971.

And I also believe that she is the “Greenfield woman” because her letter to investigators completely supported McDougall’s witness statement down to the work jacket and second man. Yet, no one else saw the same thing.

Her account does not make sense. She said she saw the vehicle parked on the east side of State Road 9 facing south. Why would the car be parked facing south? The boy in the car could have escaped while both men were out of the vehicle. Also, if the killer took one of Gray’s possible routes, he would have come into Greenfield at State Road 9 NORTH of the cemetery on I-40. I think the female witness lied in her letter to investigators to support McDougall.

I’d like to know what time of the morning she allegedly witnessed the two men with Mike. Was it still dark out? If it were, she would not have been able to see the boy’s “wild frightful expression.” It almost had to be dark out because the coroner estimated the time of death at 6:30 a.m. According to both Oct. 3, 1970, Indy Star and the website, Weather Underground, sunrise on Oct. 3 was at 7:44 a.m. Weather Underground reported that Civil twilight was at 7:18 a.m., nautical twilight at 6:46, and astronomical twilight at 6:15. So, I’m thinking it was dark, so she could not have seen anything inside the vehicle.

The woman could have phoned in the tip anonymously instead of a letter, but many people wrote tips versus calling. So, I guess that was normal back then. What I want to know is: did the police compare her handwriting to the letter written on the 1st anniversary of Mike’s murder? According to the author of that letter, “Someone else is writing this, not me.“

Where was Mike killed? Police never found a substantial amount of blood at the Johnson residence or the body location. I’m guessing in the killer’s car, so I wonder if McDougall had disposed of a vehicle, replacing it with another sometime after the killing.

Mike was kidnapped around 5 a.m. and died at 6:30 a.m. We have 1.5 hours unaccounted for, so what happened to Mike during this period?

I bet if police had checked, they would have discovered that McDougall was late to work on Oct. 3, 1970, or took the day off.

I also wonder what the current homeowners of the McDougall residence would find if someone opened up the wall where McDougall allegedly put the murder weapon and clothes.