MILLSTADT — Decades before the Villisca ax murders shocked a small Iowa community in June 1912 and the gruesome carnage the Axeman of New Orleans left behind six years later, an Illinois family was slaughtered by an unidentified killer one spring night in 1874.

At the junction of Highway 158 and 163 sits the small community of Millstadt in St. Clair County. St. Clair was established as a Northwest Territory county on April 27, 1790, by Gov. Arthur St. Clair, a Scottish-American Revolutionary War general-turned-politician. U.S. Congress created Northwest Territory in 1787, subsequently organizing it into five states – Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

Illinois officially became a state on Dec. 3, 1818. German immigrants began arriving in the 1830s, most coming after the German revolution of 1848. The Mythic Mississippi Project at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign reports, “Of the nearly 1.8 million residents of Illinois in 1860, nearly 325,000 were of foreign birth. Germans were the largest ethnic group, with 130,000 people, nearly eight percent of the state’s total population.”

The Germans came from various backgrounds. Many were skilled laborers and tradesmen, while others “worked as butchers, bakers, shoemakers, furniture and wagon builders, and cigar makers.”

Carl Friedrich Augustus Stelzriede was born in Südhemmern, Kreis Minden-Lübbecke, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany, in 1837, to Carl Franz Heinrich Stelzriede and Maria Louise Horstmann Stelzrieide.

Maria Stelzriede had given birth to three other sons: Christian Friedrich and Friedrich Christian in 1834 and Christian Heinrich in 1840. They died between 1838 and 1841, leaving Stelzriede an only child.

Stelzriede and his parents immigrated to the U.S. in 1844 and ultimately settled in Saxtown. Maria Stelzriede passed away in 1866 at age 62.

A few years later, the U.S. suffered an economic depression, the Panic of 1873, that lasted until 1879.

Since the end of the Civil War, railroad construction in the United States had been booming. Between 1866 and 1873, 35,000 miles of new track were laid across the country. Railroads were the nation’s largest non-agricultural employer. Banks and other industries were putting their money in railroads. So when the banking firm of Jay Cooke and Company, a firm heavily invested in railroad construction, closed its doors on September 18, 1873, a major economic panic swept the nation.

Saxtown residents struggled to survive through farming and other means but remained a tight-knit community.

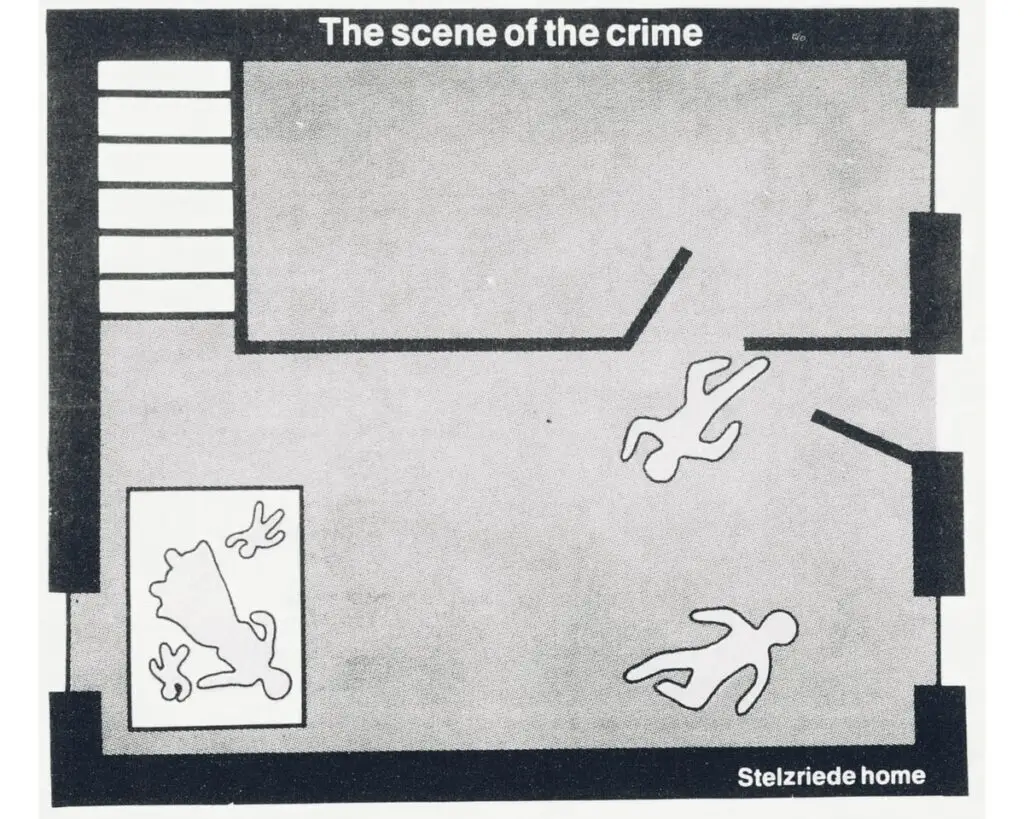

Stelzriede, his wife Anna, and their two children, Carl Heinrich, 2, and Anna, seven months old, resided at what is now 5007 Bohleysville Rd., Millstadt. The home was a one-story, three-room log cabin facing east and set back from the road.

After his mother’s death, Stelzriede’s father moved in with him and his family. They resided in one room used as a sleeping apartment while the elder Stelzriede occupied the adjoining room.

At 5 p.m. on March 20, 1874, a neighbor, Benjamin Schneider, went to the Stelzriedes to inquire about potato seeds he had purchased from the elder Stelzriede, who never delivered them. As Schneider approached the property, he noticed the Stelzriedes were not busy attending to chores and their farm animals as usual.

Schneider knocked on the front door and waited for someone to answer, but no one did. He peeked in the windows but did not see anyone. Schneider decided to return to the front door and walk inside.

Schneider found Stelzriede, 36, lying near his bedroom door in a pool of blood, his skull crushed and throat severed. Three of Stelzriede’s fingers had been hacked off during a struggle with the killer and were lying nearby.

Anna Stelzriede, 28, was on the bed in the same room. Her skull was crushed, and her throat was cut, too. Baby Anna lay dead in her mother’s arms. The Advocate described the infant as having “flaxen hair and blue eyes, its head cut open.” Both appeared to have died while sleeping.

Little Carl, three years old, lay beside his mother and sister. His face was “unrecognizable by the mass of blood which covered it,” the newspaper said.

Schneider did not look around further and bolted to the nearest magistrate. Some reports say he first ran to the neighbors, but they were too frightened to go to the Stelzriede home.

When a county deputy and coroner arrived, they found the elder Stelzriede, 64, on the floor a few steps from the door to his son’s room, which suggested he had awoken during the attack on his son and went to help him. The killer forcefully struck Carl Stelzriede, nearly decapitating him. The Chicago Tribune reported shortly after the crime that one of Carl Stelzriede’s hands “held a jacket, which seems he was in the act of putting on when the murderer killed him.”

The Stelzriede family dog named Monk was lying calm and uninjured near the bodies. Monk was said to be aggressive toward strangers, so the police believed the dog knew the killer.

According to The Newton Press, four victims had their sleeping clothes on, whereas Stelzriede wore pantaloons. Police believed that somebody killed the family during the night on March 19, 1874.

Overall, about 300 people showed up at the crime scene once word spread of the murders, and news of the horrific crime made its way across newspapers nationwide.

Police originally said that chests and drawers were open and the contents scattered on the floor. Stelzriede had received $130 cash from selling wheat, which was considered missing from the home. Both turned out to be untrue.

Police pondered whether an inheritance was the motive.

However, the killer had been taken very little from the home. They squelched the robbery theory and decided the killings were personal.

There were eight suspects in the ax murders. Some accounts state authorities arrested two men, and others report the police never apprehended anyone.

Frederick Boeltz and John Afkhen had long-running feuds with Stelzriede and had previously worked for the family.

Police found footprints outside leading away from the murder home. “Marks made by a dragging axe and footprints made by boot heels shod with nails” were found in the yard. Police also found tobacco covered in blood. Authorities believed the killer suffered an injury during the attack and used the tobacco to staunch the blood by pressing it against the wound,” wrote Heidi Wiechert in the Belleville News-Democrat.

Police followed the footprints, leading to the home of 35-year-old Boeltz, who was married to Anna Stelzriede’s sister. Boeltz had borrowed $200 from the Stelzriedes but failed to pay it back.

After initially resisting arrest, Sheriff Jim Hughes charged Boeltz with murder. The Advocate reported he “almost fainted at the ghastly sight” when shown pictures of the victims’ bodies at his trial. The jury found Boeltz not guilty. He later sued the Stelzriede estate and was awarded $400, KMOV stated. He left Saxtown and never returned.

Authorities initially thought Afkhen was Boeltz’s accomplice. He was a “half-wit” grubber and handyman with a fierce temper. Many residents feared him.

Mark Westoff, former president of the St. Clair County Historical Society, said in 1988: “A grubber was the guy who cleared the field after the trees were cut down. He [Akfhen] dug out the roots of the trees.”

Afkhen had bright red hair. According to several sources, the elder Stelzriede was clutching a clump of hair the same color when police found his body, not his jacket, as the Tribune initially reported.

Deputies arrested Afkhen and put him in a separate cell from Boeltz. Authorities eventually let him go, and he continued living in Saxtown. Afkhen always carried an expensive gold pocket watch. When someone asked him where he got such an expensive watch on his salary, he merely smiled in response. Stelzriede had owned an identical pocket watch.

On March 22, 1874, over 1,000 people attended the Stelzriede family’s burial at Freivogel Cemetery. Shortly after, relatives in Germany sent money to have the family remains relocated to Belleville’s Walnut Hill Cemetery. But for whatever weird reasons, armed Saxtown residents prevented a grave digger from moving the bodies. Some reports say officials at Zion Evangelical Church, who owned the cemetery, forbade the removal. The victims rest in five unmarked graves in the northwest corner of Freivogel Cemetery. Nevertheless, a 9-foot obelisk stands in the family’s honor at Walnut Hill.

The Stelzriede murder cabin was demolished in 1954, but the barn still stands.

In 1988, Michelle Meehan of the News-Democrat interviewed Randy Eckert on the 114th anniversary of the family murder. Eckert bought the land and built a small house on the site.

Eckert and his wife moved into the home and planned to stay for two years. However, they began experiencing strange phenomena after moving into the new residence, almost always occurring around the anniversary of the quintuple murder.

Eckert told Meehan of one particular incident.

“We were sleeping, and we had this small dog, and the dog woke us up. It was just shivering like crazy,” Eckert said. “My wife got up and said, ‘Do you hear something?’ and I said, ‘Yeah.’ Then all of a sudden, we heard a dog howling from like 100 years ago.

“Then we heard someone pounding on the door. The door to the house has glass windows and it’s a very small house. One step out of the bedroom and you can see the door, and that door was bounding. Somebody was beating on that door,” he said. “I walked straight to the door, never seeing anybody out the window, and the closer I got, the sound disappeared. When I got to the door, there was nobody anywhere.”

The Eckerts moved out and rented the home out to tenants.

“I always tell renters the history of the house,” he said. “You have to be in the right frame of mind to live in there.”

Eckert said he “probably had a dozen people move out.”

Chris Nauman lived in the home in the early 1990s.

“It was 6 o’clock in the morning, and there was a loud knock on the door. At the same time, my girlfriend heard someone walking up the steps in our basement.” Nauman, startled by the sounds, quickly checked the front door and the basement stairs but found no sign of visitors or intruders. The next day, he shared his story with Randy Eckert, asking him about the anniversary of the Steltzenreide murders. Eckert confirmed it for him – the ghostly happenings had taken place on March 19, the anniversary of the murders.

– Troy Taylor, “Bloody Illinois.” Retrieved from https://www.americanhauntingsink.com/millstadt

Eckert later had another home built adjacent to the murder site and currently resides there.

Nicholas J.C. Pistor wrote “The Ax Murders of Saxtown” (affiliate link) after spending 10 years researching the crime. Pistor is a former reporter at St. Louis Dispatch and has worked as a consultant for CBS’ “48 Hours.”

Notes: There are spelling variations with the Stelzriede name – Steltzenriede, Stelzereide, and Stelzeriede. TCarl Stelzriede’s has been reported as anywhere from 64 to 80. However, his Find a Grave memorial gives his birth date, which put him at age 64 at death. Likewise, Stelzriede’s age has been reported as young as 28. He was 36. There are also many discrepancies between accounts of the murders. I have not read Pistor’s book, but I am contemplating it because it is likely the most accurate. If I do, I’ll update this article.

True Crime Diva’s Thoughts

I live in Illinois but have never been farther south than the St. Louis area. But if I ever head that way, I’m driving through Millstadt to see those buildings!

It seems to me that Akfhen and Boeltz killed the Stelzriede family. I don’t know what more proof the police needed in 1874. The footprints led to Boeltz’s home, and the elder Carl had a clump of bright red hair, likely Akfhen’s hair, in his hand, assuming this is true. The Tribune reported Carl held a jacket in one of his hands.

Afkhen reportedly had a gold watch identical to the one Carl owned. That’s more than a coincidence.

The Newton Press article stated that Akfhen was the person who notified Boeltz of the murders. So, Akfhen could have walked from the Stelzriede home to Boeltz’s house to throw the police off him and pin the killings on Boeltz.

Akfhen had the personality of a killer – cold and mean – as many people feared him. He was a grubber and could swing an ax forcefully, although police never determined if the murder weapon was an ax or knife; they never found it. I guess authorities could discern by the victims’ injuries that the killer was left-handed.

Schneider was left-handed, and police briefly looked at him. But they never charged him. One local said in 1988 that he believed two brothers killed the family, but he did not elaborate.

Who was the last to see the family alive? Schneider found the bodies around 5 p.m., and somebody killed them the night before (March 19).

The killings were overkill, so whoever killed them was filled with rage. Strangely, the killer left Monk unharmed. So, the killer murdered a baby and toddler but left a dog alive? That makes no sense. Was the dog outside during the murders, and did the killer let him inside the house before he left?