The Congressional Judiciary Committee last month held a four-hour hearing, “Victims of Violent Crime in Manhattan” to understand better why New York City’s crime rates were “out of control” and what was wrong with its criminal justice system. Putting aside how the hearing spent some time specifically on any possible role Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg played in New York City’s crime rates, the hearing itself was not a bad idea. The problem was the Committee held its hearings about 30 years too late.

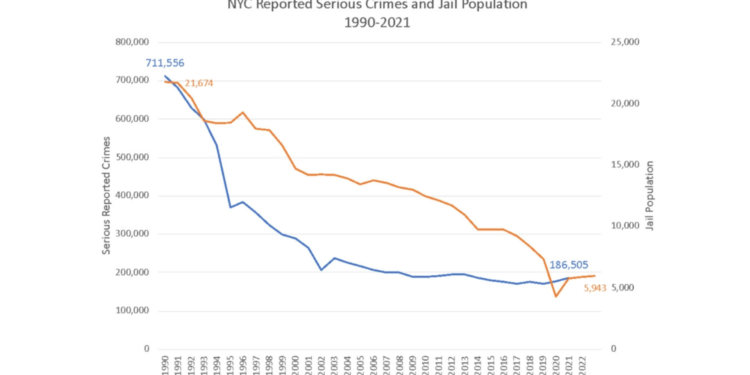

In 1990, there were over 700,000 serious crimes reported to police with over 2,500 murders. Rikers Island was overflowing with almost 22,000 prisoners, many of whom were housed in hastily constructed large outdoor tents called “Sprungs” or on floating barges.

But by 2022, the total number of crimes had dramatically declined to under 200,000 with murders down to 438, a remarkable 71% reduction in violent crime and 82% decline in murder.

These massive reductions in violent crime and murders were about twice the decline for the nation during the same time period.

More remarkably, as the crime and murder rates declined, so did the jail population. Currently, there are less than 6,000 people incarcerated—a reduction of 16,000 or 73% in the jail population. Clearly, NYC has shown that crime and jail populations can be drastically reduced at the same time.

Both the current NYC murder rate (4.5 per 100,000) and the jail incarceration rate (66 per 100,000) are well below the national rates (6.5 murder and 192 jail rates). NYC also has one of the lowest incarceration rates for Blacks in the nation.

If the rest of the country could match New York City’s rates of Black Incarceration, the national jail population would decline by about 400,000 and there would be about 5,000 fewer murders per year.

Rather than disparaging NYC, the House Committee should examine what factors and policies have produced these amazing results. It is true that since 1990, crime has dropped significantly throughout the nation largely due to changes in socio-economic-demographic factors like a declining birthrate, a smaller household size, an aging population, and lower inflation rates.

The crime decline in NYC is still more than twice that of the national reduction. But there are specific policies that have accelerated NYC’s declines in crime and jail population.

These include strict gun control laws, the pioneering NYPD COMPStat analytic program, a pretrial services agency with a valid risk assessment system, proper supervision of released defendants, and the significant funding of community-based programs and services.

Despite these achievements, as with every other U.S. city and state, there was an uptick in crime in 2021 which has been linked to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and an associated increase in inflation – not bail reform. As COVID-19 and inflation have subsided, crime is again declining in New York City and elsewhere.

The nation can learn much from New York City on how to reduce crime and the jail population. Perhaps the Judiciary Committee can soon return to Manhattan and hold a more timely hearing on what was accomplished in New York City and how to replicate it nationally?

James Austin is the founder of the JFA Institute which he formed in 2003. Prior to that, he was the Director of the Institute of Crime, Justice and Corrections at the George Washington University, and Executive Vice President for the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. He began his career in corrections with the Illinois Department of Corrections at Stateville and Joliet Penitentiaries. He is the co-author with John Irwin, It’s About Time: America’s Imprisonment Binge (Wadsworth, Cengage Learning, 2012)

Michael Jacobson is ISLG’s founding Executive Director as well as a sociology professor at the CUNY Graduate Center (GC). Prior to joining CUNY in May 2013 to help create ISLG, Michael was president of the Vera Institute of Justice, serving from 2005 to 2013. He is the author of Downsizing Prisons: How to Reduce Crime and End Mass Incarceration (New York University Press 2005). He was New York City correction commissioner from 1995 to 1998, New York City probation commissioner from 1992 to 1996, and worked in the New York City Office of Management and Budget from 1984 to 1992 where he was a deputy budget director.