Twenty-four people have been put to death in the US this year with the executions all taking place in five states as of December 7. The death penalty has always been, and continues to be, a regional punishment favored in the most violent, politically conservative states: the Confederate states and their bordering neighbors.

Yet this region of the country is considered the most religious, especially with evangelical Christians. So why is there so much bloodletting in these church-going states?

The death penalty, I believe, is a diseased punishment rooted in the tradition of religion. Perhaps that explains why the punishment is infected with systemic racism and unfairness—both of which have tragic legacies in the Southern Confederacy.

Of the 23 men and one woman executed, eight had spent more than three decades in the shadow of death. What purpose, other than callous revenge, did their executions serve?

The Tragic Story of Terence Andrus

If one had listened closely to the silence in the death chambers moments before the executions got underway, they would have heard Jesus Christ, the savior of Christians, say: “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”

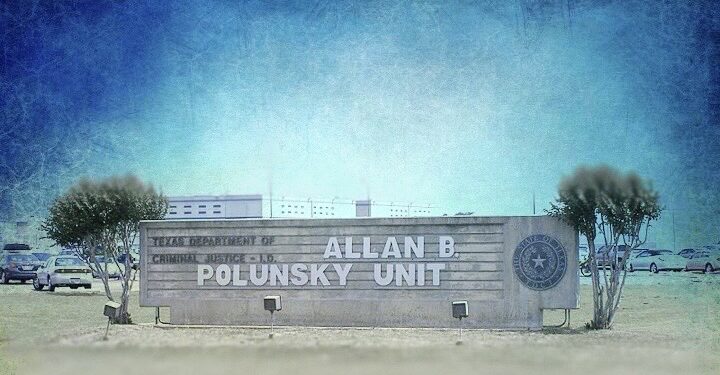

One man, 34-year-old Terence Andrus, decided not to wait for Jesus to forgive those who wanted his execution. On January 21, 2023, he hanged himself on death row at the Polunsky Unit in Livingston, Texas. That did not end his tragic story.

Andrus’ decision to end his own life rather than allow the State of Texas to take it came roughly six months after the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the very death sentence it had just two years earlier (June 2020) declared unlawful.

On February 1, 2023, the Death Penalty Information Center reported that Andrus’ attorney, Gretchen Sween, told the Los Angeles Times that the latest Supreme Court denial left her client a “broken” man “careening toward the abyss.”

Andrus was convicted and sentenced to death in 2012 for a 2008 double murder he committed at age 20 during a carjacking while high on PCP-laced marijuana. The jury that sentenced him to death did not hear evidence that he had a mood disorder psychosis; or that at age 16, he was placed in a cold, filthy solitary confinement cell at a juvenile detention facility where he was pumped with a steady diet of psychotropic drugs; or that he had a history of parental neglect, suicidal tendencies, and self-mutilations.

In its June 2020 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) to consider whether the substandard performance provided by Andrus’ defense counsel during the death penalty phase of the trial created sufficient “prejudice” to constitute a Sixth Amendment ineffective assistance of counsel claim.

In September 2017, the judge who presided over Andrus’ trial had already drawn the conclusion that the defense counsel’s deficient performance was so egregious that it did in fact prejudice Andrus’ right to a fair punishment hearing.

But the CCA in February 2019 rejected the trial judge’s recommendations for a new sentencing hearing and instead upheld Andrus’ death sentence.

Andrus sought, and secured, certiorari review in the Supreme Court; and in its June 2020 decision, the Court gave factual credence to the trial judge’s thorough treatment of the ineffective assistance claim:

“After considering all the evidence at the hearing, the Texas trial court concluded that Andrus’ counsel had been ineffective for ‘failing to investigate and present mitigating evidence regarding [Andrus’] abusive and neglectful childhood.’ The court observed that the reason Andrus’ jury did not hear ‘relevant, available and persuasive mitigating evidence’ was that trial counsel had ‘fail[ed] to investigate and present all other mitigating evidence.’ The court explained that ‘there [is] ample mitigating evidence which could have, and should have, been presented at the punishment phase of [Andrus’] trial.’ For that reason, the court concluded that counsel had been constitutionally ineffective and that habeas relief, in the form of a new punishment trial, was warranted.”

The High Court then set out the specific reasons why it wanted the CCA to reexamine the “prejudice” of Andrus’ ineffective assistance.

That June 2020 decision was a sharply divided 5-4 ruling with the four dissenting justices favoring a politically driven policy of paying judicial deference to decisions rendered the states’ highest courts in capital cases. Their dissent probably emboldened, if not encouraged the CCA to rebuff the Supreme Court’s implied suggestion that Andrus’ defense attorney had been so deficient that prejudice should be assumed.

In its own sharply divided decision, the CCA ruled on May 21, 2021 that Andrus had failed to sufficiently meet the prejudice component necessary to make out an ineffective assistance of counsel.

In other words, the CCA ruled that had the jury heard all the mitigating evidence as described by the Supreme Court, not one juror would have recommended a sentence less than death.

Andrus’ attorney, Gretchen Sween, once again sought and secured certiorari review before the Supreme Court.

A Bizarre Stand by The Supreme Court

At this point in Andrus’ tortured post-conviction history, he had ten judges—five Supreme Court justices, four CCA judges, and the trial judge—who believed he had received ineffective assistance of counsel during the death penalty phase of his trial.

But in a bizarre twist, the Supreme Court turned its back on its own June 2020 decision and refused to hear Andrus’ second certiorari, effectively allowing his death penalty to stand as the CCA had ruled.

Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justices Kagan and Breyer, issued a strongly worded 25-page dissent which, in part, reads:

“This Court held that counsel had rendered constitutionally deficient performance. That conclusion was based on an ‘apparent ‘tidal wave’ of ‘compelling’ and ‘powerful mitigating evidence’ in the habeas record, none of which counsel presented to the jury…On remand, the Court of Criminal Appeals, in a divided 5-to-4 decision, failed to follow this Court’s ruling… As a result, the dissenting judges below explained, the Texas court’s opinion was irreconcilable with this Court’s prior decision and barred by vertical stare decisis and the law of the case...I agree with the dissenting judges below. Andrus’ case cries out for intervention, and it is particularly vital that this Court act when necessary to protect against defiance of its precedents. The Court, however, denies certiorari. I would summarily reverse, and I respectfully dissent from the Court’s failure to do so.”

The brutal politics that now influence the Supreme Court decision-making left a psychologically disturbed condemned man with no other options than to face death in the Texas death chamber or face death by hanging himself in a solitary death cell.

That’s the true nature of the death penalty. The Confederate states, and their death penalty-worshipping cohorts, routinely execute the mentally ill, the innocent, the unconstitutionally convicted, and the marginalized who could not afford to hire effective counsel.

Terence Andrus chose to hang himself the day before Christian evangelicals packed the church pews across Texas on Sunday morning to give praise to Jesus Christ who had this to say about the executioners they support: “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”