A little over a year ago, Michael Ardizone complained to jail officials in Pike County, Mississippi, that he’d been locked up for more than a year with no attorney and no indictment on his drug possession case.

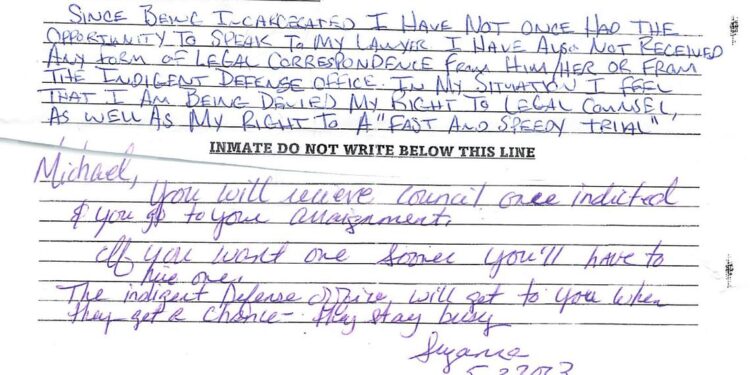

“I feel that I am being denied my right to legal counsel,” Ardizone wrote in April 2023, according to documents he later filed in federal court in an attempt to get out of jail.

A jail official hand-wrote a brief response: “You will receive counsel once indicted. If you want to see one sooner, you’ll have to hire one.”

Two months later, in July, the Mississippi Supreme Court imposed new public defense requirements. In all 82 counties, people like Ardizone could no longer sit in jail without a lawyer even if they hadn’t been indicted, the court said. Instead, counties had to provide free legal representation to poor defendants shortly after an arrest and throughout the time spent waiting for an indictment from a grand jury.

Yet Ardizone remained in jail without a lawyer for six more months. He was indicted in November and was finally provided legal counsel in January. He has pleaded not guilty.

Then, in February, Circuit Judge Michael Taylor found that the Pike County Jail was full of more people like Ardizone. After a review of jail records, Taylor appointed attorneys for 44 people without lawyers. The average time in jail for those defendants was 223 days. Three had been locked up for more than a year and 23 for more than six months, according to analysis by The Marshall Project – Jackson.

The number of defendants without lawyers in Pike County was “pretty shocking,” Taylor told The Marshall Project – Jackson.

As Pike and other Mississippi counties have struggled to implement last year’s new rule about when poor defendants should be provided lawyers, reporting by The Marshall Project, The Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal and ProPublica identified even more fundamental public defense problems in the state. In one north Mississippi court, judges appointed lawyers for only 20% of felony defendants who appeared before them in 2022 and forced one defendant in 2023 to represent herself during a key hearing despite her requests for a court-appointed lawyer.

Statewide reform remains elusive.

Despite initial momentum in the Mississippi Legislature this year, lawmakers eventually rejected a bill to authorize the development of new public defense guidelines for local officials.

Mississippi requires that local governments bear almost the entire burden of creating, funding and managing indigent defense. That’s not a simple task. In Mississippi’s legal system, criminal defendants may move through as many as three different court systems, each with its own system of public defense, as they go from arrest to a plea deal or trial verdict.

The state, however, fails to evaluate or even monitor whether local governments and courts are providing lawyers to defendants who cannot afford them.

Mississippi is one of only eight states that rely on local officials to fund and deliver almost all public defense for people facing trial, according to the Sixth Amendment Center, a Boston-based nonprofit research center that advises states about how to strengthen public defense.

However, even some of those other states with local indigent defense systems like Mississippi’s have created some oversight measures, including similarly rural states with conservative political leadership, said David Carroll, director of the center.

This year, for example, South Dakota empowered a statewide commission to regulate how local indigent defense operates.

“Mississippi,” said Carroll, “is really getting isolated.”

State officials are aware that local compliance with 2023’s new rule from the state Supreme Court as well as older and even more basic public defense rules is often inadequate. A state high court justice and other expert witnesses said as much at a legislative hearing last fall.

But during this year’s session, lawmakers considered only the most modest of reforms — and even those failed.

Senate Bill 2260 would have authorized Mississippi’s state public defender — a gubernatorial appointee — to issue performance standards for local public defense systems throughout the state, subject to approval by the state Supreme Court.

The bill’s sponsor, Sen. Brice Wiggins, a Republican from the state’s Gulf Coast region, said during the legislative debate that the bill would have encouraged “consistent, high-level indigent defense in the state.”

Describing the current state of public defense in Mississippi, Wiggins, a former assistant district attorney, told fellow lawmakers that “there’s really no standards for indigent defense and so you get different levels of defense, to say the least, throughout the state.”

State Public Defender André de Gruy told The Marshall Project – Jackson that had the bill passed, he would have convened an advisory panel and worked to standardize indigency criteria in addition to performance expectations for indigent defense counsel. He cited conversations with judges and reporting by The Marshall Project – Jackson as showing the need for such standards.

The bill, however, lacked an enforcement mechanism, a shortcoming Wiggins acknowledged during the Senate debate. It also failed to provide money to the counties to help meet the new standards.

State Sen. Daniel Sparks, a lawyer and Republican from the state’s northeastern corner, objected to the bill.

“So we’re going to allow the state public defender, one individual, to promulgate and implement standards that are going to be binding on all 82 counties?” Sparks asked.

The second-term lawmaker has for years represented indigent defendants for courts in Tishomingo County. He noted that the counties pay for public defense services, not the state.

Despite objections from Sparks, the bill passed the state Senate with a large, bipartisan majority — 44 yes votes, with only five votes in opposition. Sparks, however, used a parliamentary procedure to halt the bill’s progress. The bill eventually died because Wiggins never moved for the necessary vote to overcome the stalling tactic.

De Gruy did suggest lawmakers amend the bill to empower a commission rather than let de Gruy alone craft the standards. He said he told Sparks as much to salvage the bill.

Wiggins told The Marshall Project – Jackson he may revisit the issue in a future session — which would be next year at the earliest.

For his part, Sparks told the news organization that while “sitting in jail without an attorney for 223 days is not how the system is supposed to function,” he does not believe statewide commissions or officials can most effectively address such problems in the local systems.

A version of the same bill has passed the state House in prior years, only to die without any vote in the Senate.

Another bill introduced this year would have exempted public defenders from the fees required to access the Mississippi Electronic Courts system. Prosecutors are already exempt from the fees. Despite being approved by a committee, the proposal later died.

Yet another failed proposal would have boosted pay for some of the lowest-paid lawyers who take on indigent defendants.

At least since the mid-1990s, some state judicial officials as well as prosecutors, defense attorneys and civil rights advocates have urged reforms while criticizing Mississippi’s public defense system, but the Legislature has never made changes. A little over two decades ago, some counties unsuccessfully sued to force the state to provide funding.

With no new laws, the Mississippi Supreme Court has tried to fill in some gaps, using its administrative power over lower courts to impose basic rules around public defense.

Last year’s rule from the high court, for example, was intended to prevent what happened to Ardizone, who spent almost 600 days in Pike County’s jail without a lawyer, held on a $4,000 bond for much of that time.

Legal advocates who asked the court for the new rule highlighted similar cases to support their claim that legal representation for poor defendants is important early in a case.

This March, Judge Taylor, who presides over three counties in southwest Mississippi, finally ordered Ardizone released without bail, pending trial on his charge of possessing less than two grams of methamphetamine.

If Ardizone had gotten a lawyer earlier, that lawyer could have asked a prosecutor why Ardizone’s indictment was taking so long, tried to negotiate an early plea deal or requested that a judge do what Taylor ended up doing — release Ardizone without bail.

According to Taylor, the senior circuit judge in his district, he has now imposed a system over Pike County’s tangle of local courts to ensure that poor felony defendants always have a lawyer before an indictment. He believes that cases like Ardizone’s have shown the benefit of such representation to the local public defenders, one of whom had asked the state Supreme Court not to issue the rule.

“The public defenders have been very engaged,” Taylor said. “Once you laid it all out, they realized the importance of continuing representation.”

Pike County’s chief public defender Paul Luckett, who also represents Ardizone, did not respond to requests for comment.

But Pike County is not the only county to delay implementation of new public defense protections. Last year, The Marshall Project, the Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal and ProPublica found that after the high court required that indigent defendants always have legal representation, even before an indictment, many courts weren’t prepared to comply.

It’s not the first time the state Supreme Court has had limited success in its efforts to reshape the landscape of public defense. The news organizations also found that a 2017 rule from the Mississippi Supreme Court, which was intended to boost transparency and accountability for local defense systems, has been ignored by almost all the state’s local courts.

Against this backdrop, a state Supreme Court justice said during a legislative hearing last fall that the high court’s ability to enforce compliance with its own rules was limited.

Instead, Justice Jim Kitchens called on Mississippi lawmakers to finally take action and fix problems the Mississippi Supreme Court has been unable to remedy.

“The playing field is far from level,” Kitchens said. “You are the great levelers.”