The “How Many Stops Act” is a go.

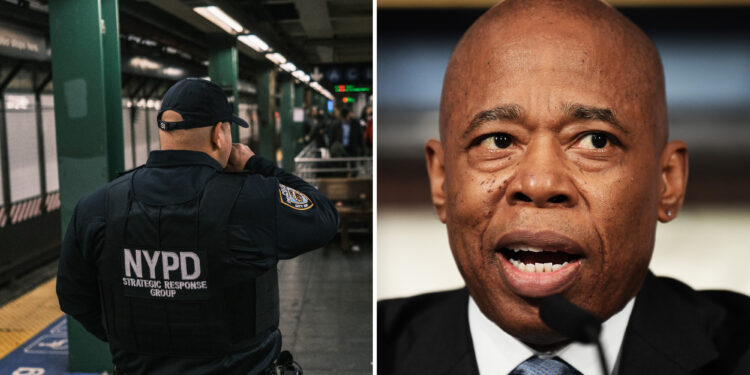

The controversial new city law requiring NYPD cops to file reports on all low-level investigative stops with New Yorkers officially kicked off Monday — and rank-and-file officers weren’t happy.

“A huge pain in the ass,” one law-enforcement source told The Post.

The City Council successively pushed through the bill in January after Mayor Eric Adams pulled out all the stops — including a veto — to kill it.

Adams, NYPD officials, police union leaders and many everyday New Yorkers argued the law would bog down cops in excessive paperwork — a fear reiterated by the mayor Monday.

“We need our officers on patrol, not doing paperwork, but it’s the law, and we must follow the law,” Adams told 1010 WINS.

Police officials said the new reports will be filed on by smartphones.

An internal NYPD order obtained by The Post details how much paperwork cops are expected to do under the law.

Uniformed cops now have to document the “aggregate number” of Level 1 encounters — which are stops in which they request information from people — at the end of their shifts, according to the order.

Those broad reports counting the lowest levels of stops won’t apply to Level 2 encounters, in which cops ask accusatory questions or seek consent for a search, the order states.

For each of those next-highest level of investigative stop, officers will have to fill out individual reports, the order states.

“Officers will be using forms on their smartphones to track the required data, which will be aggregated and made public on a quarterly basis,” an NYPD spokesperson said.

The internal order makes clear that cops don’t have to report on casual encounters with the public unless officers develop reasons to collect information or suspicion that a crime has been committed.

“An investigative encounter does not include a casual conversation between a member of the Department and a member of the public,” it states.

Law enforcement sources couldn’t immediately say how much work the new smartphone-based reports will add to cops’ days.

But they raised a host of other grievances, including over its requirement that cops report the “apparent” race or ethnicity of people they stop.

“One of the most racist things you can ask a cop to do is assume someone’s race based on their appearance,” a source said.

“Who are we to assume someone’s race?”

Another law enforcement source worried the stop reports will end up in the hands of the NYPD’s internal watchdog — the Civilian Complaint Review Board — and of progressive Council members.

“This is really designed for CCRB to use against [the police department] to articulate some sort of bias,” the source said. “The Council will likely weaponize this data.”

The law’s supporters, such as Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, contended collecting such information is necessary to provide much-needed NYPD transparency, hold cops accountable for unlawful stops and tamp down racial profiling.

“For too long, unreported stops have allowed NYPD to harass marginalized communities with impunity,” said Lindsey Smith, staff attorney with the Criminal Defense Practice’s Special Litigation Unit at The Legal Aid Society.

“The implementation of the How Many Stops Law is critical for transparency and improved reporting of stops of civilians.”

— Additional reporting by Amanda Woods