As ads attacking presumptive Democratic presidential nominee Kamala Harris began running in battleground states this week, a familiar theme emerged: “She let an MS-13 gang member go, who then murdered a father and his two sons,” warns the narrator in a Make America Great Again Inc. PAC ad, referring to her record as district attorney in San Francisco. “She agreed to release another felon, who then committed murder.” In other words, Trump supporters are making good on their plans to “Willie Horton” Harris — a reference to a 1988 television spot that changed the politics of criminal justice for decades.

What does it mean to “Willie Horton” a political candidate?

In 2015, The Marshall Project dug deep into the history of that notorious ad to find out, talking at length to William Horton himself. At that time, it was not outlandish to ask whether this particular type of ad — sensationalizing isolated bad acts by people (usually people of color) released from prisons or jails, and pinning the blame for them on individual candidates — had run its course. After the very public police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Freddie Gray in Baltimore, and the nation’s reckoning with mass incarceration and police brutality, politicians were newly, tentatively, willing to explore bold criminal justice reforms. But the past is never really past, and 1988 is beginning to echo in the halls of 2024. As for the Trump PAC ad, for the record: The MS-13 gang member the ad refers to was let go because, Harris’ office said at the time, there wasn’t enough evidence to charge him with a crime; months later, he did commit a triple homicide. It’s not clear what case the “felon who then committed murder” refers to.

Here are three key things to know about the history of “Willie Horton” attack ads:

“Willie Horton” was the subject of a 1988 political ad created by supporters of then-vice president and Republican presidential candidate George H. W. Bush.

William Horton had been serving a life sentence for murder in a Massachusetts prison when he was released temporarily on a furlough and didn’t return. While on the run, he committed a brutal home invasion and rape. Bush was running for the presidency against Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, a Democrat, and the ad pinned the blame for Horton’s crimes on Dukakis’ furlough policy.

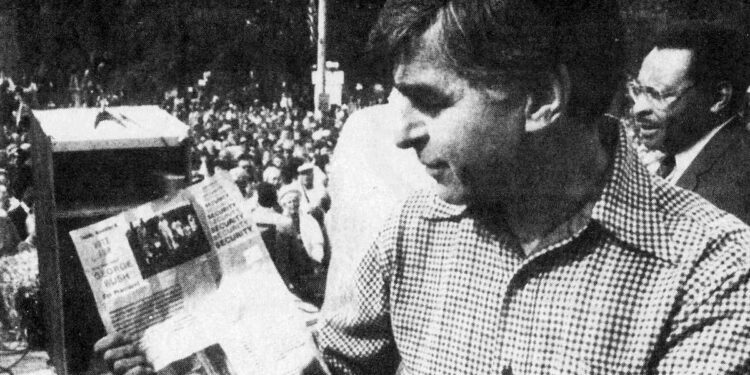

“Dukakis not only opposes the death penalty,” the narrator intoned, “he allowed first-degree murderers to have weekend passes from prison.” A grainy black-and-white photo of Horton appeared on the screen, with heavy-lidded eyes and an unkempt beard. The ad never mentioned Horton’s race, but it didn’t have to: Amid historically high violent crime rates, this image of Horton played to White fears and deeply rooted racist stereotypes.

Later, Horton told me that photo was taken after he had spent several weeks in solitary confinement, recovering from gunshot wounds and the multiple resulting surgeries. Looking at that picture, “I would have been scared of me too,” he said. He also said that no one had ever called him “Willie.” He thought renaming him was political operatives’ way of leaning on more stereotypes about Black men from the South, making him seem dumb and uneducated. “I never lived up to that name that they painted with that picture, which was ‘Willie,’” he said. “That wasn’t me. That’s not even my name.”

The ad commenced the birth of the modern-day negative presidential campaign, commentators said.

The ad was very effective: George H. W. Bush came from behind to sweep the 1988 presidential election, winning 40 states in the Electoral College. Time magazine called Horton “Bush’s Most Valuable Player.” Prior to “Willie Horton,” bad outcomes in the criminal justice system rarely became fodder for political attacks. Less than 20 years earlier, a man on a furlough from the California prison system in the 1970s murdered a police officer under the oversight of then-Gov. Ronald Reagan, who went on to become president in a landslide, with Bush as vice president. At the time, Reagan defended the state’s furlough program, arguing that more than 200,000 people had had successful furloughs from prison, but “obviously you can’t be perfect.”

In the wake of the 1988 campaign, it’s become a given that if someone released from prison commits a bad act, it’s a political liability for whoever was in charge at the time of the release. “Clearly the Willie Horton ad was a very important lesson for politicians,” Ronald Weich, who worked at the U.S. Sentencing Commission in 1988, and later as legal counsel for several senators, told The Marshall Project in 2015. “They learned a bad lesson: not to go out on a limb.”

The ad’s impact showed how “race and fear worked in America.”

Republican strategists had long recognized the power of using coded language to instill fear in White voters. Lee Atwater, Bush’s campaign manager, admitted as much in a 1981 interview with political scientist Alexander Lamis. Atwater said that in 1954, politicians could, and did, openly use the n-word, but that by 1968, “That hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like ‘forced busing,’ ‘states’ rights’ and all that stuff.”

That strategy translated seamlessly to 1988. “The Horton case is one of those gut issues that are values issues, particularly in the South,” Atwater told Baltimore Sun political columnist Roger Simon in 1988, “and if we hammer at these over and over, we are going to win.” He didn’t need to say out loud what “values issues” meant to Southern voters, Simon wrote later. “It succeeded because race and fear worked in America in 1988.” This type of messaging only works when it remains implicit, political scientist Tali Mendelberg wrote in her book about the Willie Horton ad. Because White people don’t want to see themselves as racist, the message loses its power once it’s revealed, Mendelberg wrote.

Jesse Jackson publicly called the Willie Horton ad racist in 1988 — to which Atwater replied, “I don’t even think many people in the south know what race Willie Horton is.” But soon it became widely acknowledged that the ad was a nakedly racial appeal. A follow-up ad that showed a more racially diverse group of people in prison jumpsuits walking through a revolving door of prison bars while a narrator intoned, “His revolving-door prison policy gave weekend furloughs to first-degree murderers” did little to dispel the feeling that these ads were appealing to White voters’ ugliest fears.

In the 2024 election, it’s already clear that the role of criminal justice will be front and center — on both sides. Harris, who spent decades as a district attorney and state attorney general, is leaning hard on her record as a top cop who went after lawbreakers and fraudsters. She’s positioning herself in contrast to Trump, who styled himself a “law and order” candidate but was recently convicted of dozens of felonies and found liable for fraud and sexual assault.

But will “Willie Horton”-style ads have the same salience in 2024 as they did in 1988? We won’t find out until November.