When I found out I was pregnant, I wanted my sister Keeley to be one of the first to know. I knew her excitement would be over the top and uncontainable. So, right after I got the positive test result at five weeks, I sent Keeley a postcard. At the time, there was no online messaging service at the prison where she was incarcerated, and I thought mail was the perfect way to break the news. My postcard said only: “I’m PREGNANT!!! ☺ Call me!”

I pictured her taking it in her hands during mail call and breaking into an elated grin, yelling to anyone within earshot, “I’m gonna be an aunt!” Each time I saw the prison number flash on my phone and heard the robotic voice asking me whether I’d accept the call, my heart sped up a little. Instead of “Hello,” I answered Keeley’s calls with “Did you get my postcard?” No, she hadn’t — so I sent another, and another. The phone calls stopped due to an extended lockdown at the prison, and five postcards later, I was nine weeks pregnant and no one besides my partner knew.

After my ultrasound that ninth week, my partner and I told our parents, asking them to keep it a secret. But of course, Keeley called me hours later and demanded (so loudly I held the phone away from my ear), “Mom says you need to tell me something! Are you pregnant?”

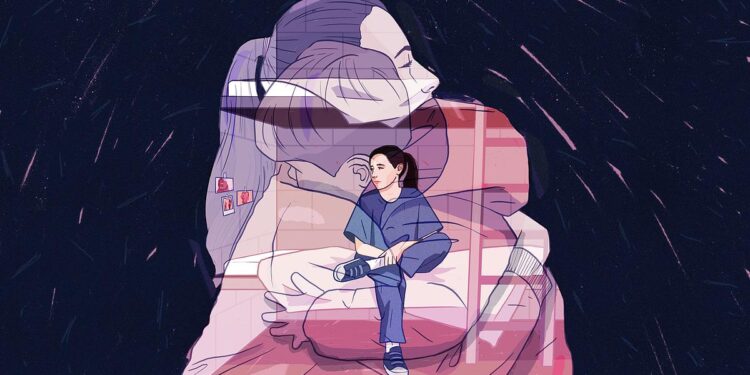

The censorship of my pregnancy announcement postcards is the least of the horrors Keeley endured while behind bars. Her own childbirth was induced at the convenience of the prison, she was shackled right after delivery, and she was torn from her baby the day after birth.

Incarceration separated Keeley from her daughter again and again. While incarcerated — on and off, over the course of 14 years — Keeley experienced violence at the hands of guards, solitary confinement, invasive strip searches, medical neglect and forced sedation.

But the fact that someone threw out five postcards telling Keeley she was going to become an aunt — one of her deepest wishes in life — says something about the everyday cruelty of the system and its casually deliberate acts to deprive people of core human joys, of excitement, of relationship: a survival need. It also deprives people of the most fundamental forms of self-determination, including choosing to have and care for children (or to not have children — abortion is even less accessible behind bars than it is on the outside).

Keeley wasn’t there to hold my child when they were born. She was not only in prison, but subjected to another lockdown, in which no one could make calls for nearly a week. When her own child was born, she hadn’t been able to make a phone call to tell us right away, either. The routine severing, the isolation inside of isolation, is part of what makes prison, prison.

I was an abolitionist before I was a parent. I already believed that the racist, ableist, classist, cis-heteropatriarchal systems of prisons and policing must be dismantled, and that we must simultaneously build well-resourced and interconnected communities that support people’s collective safety. But becoming a parent drew me even further into this basic knowledge: that if we care about kids, then we must destroy the bars and walls and chains that forcibly separate people who love each other. And we must also dedicate ourselves to abolition’s central commitment, which dovetails profoundly with caregiving: the creation and growth of practices, resources, and ways of being that are life-affirming and generative instead of death-dealing and violent.

I shared this recently — that being a mom had made me even more of an abolitionist — with another parent, someone I’d just met at the playground. (Yes, I am one of those people who wears shirts that say “Free Them All!” and “Abolish the Police” to the playground, both hoping and not hoping that someone will ask me about them.) “Doesn’t being a mom make you more scared of crime?” she said. I asked her what she meant by crime. “Violence,” she said. “Aren’t you scared of violence against your kid?”

This is one of the most understandable things in the world to be scared of. It’s what fuels my insomnia each night: the idea of something horrible happening to my child. Being an abolitionist, for me, is not about smugly or dismissively proclaiming that people shouldn’t be scared. (I don’t know any abolitionists who dismissively proclaim this, although this is the abstract picture that some have painted of us.) My worries about the safety of children — all children — are part of why I’m an abolitionist. Prison and policing are violence against kids, from youth incarceration to parental imprisonment to the ensnaring of caregivers and children in systems like electronic monitoring, forced “treatment” centers, group homes and migrant jails.

About half of people incarcerated in state prisons have children under 18, many of whom are displaced when their caregivers are incarcerated. Beyond biological parents, there are no statistics on how incarceration disrupts the entire vast web of caregivers and supporters connected with children. Family policing — otherwise known as the child “welfare” system — severs these connections further.

As parent-led abolitionist groups urge us to recognize, the carceral system is itself one of the United States’s most massive perpetrators of harm and abuse against children, particularly indigenous and other people of color, working-class, trans, queer, migrant and disabled children. Further devastation stems from the fact that carceral systems like prison, policing, family policing, migrant incarceration and electronic monitoring masquerade as protecting children — but they don’t. In addition to the fact that these systems directly harm kids, they also don’t actually prevent interpersonal violence and abuse, much of which takes place in the home.

The United States is the most incarcerated country in the world, and yet violence against children remains rampant. I recounted all this to the inquiring playground mom, trying not to sound like an angry jerk. After all, without a few critical moments of impact in my life — my sister’s incarceration, a friend’s detention and deportation, a family member’s institutionalization, and my assignment to the prison “beat” as a journalist — I might not be an abolitionist myself. I shared with her that I’m inspired by organizations imagining actual ways to end violence against kids.

But also, I told her, I’m inspired by the playground. Yes, there are frequent squabbles, but kernels of abolition in action abound. When a 3-year-old pushes or kicks or hits another 3-year-old, the kids don’t call the police. Instead, they use other strategies, from bursting into tears and shouting for a trusted loved one, to fighting back, to saying their feelings are hurt, to apologizing, to perhaps even trying to figure out a solution to the underlying problem. (“I shouldn’t have called you a reindeer monster,” I heard someone remorsefully admit yesterday.) Often, the strategies don’t work, but as longtime abolitionist organizers have taught us, abolition is, in part, about experimentation.

Adults sometimes act differently on the playground, too: When a 4-year-old hits or pushes or kicks their parent or caregiver, the adult doesn’t usually dial up the cops and turn the situation over to the carceral state. Instead, I’ve witnessed parents experimenting with many tactics — some effective, some not — to deal with harm and conflict. I won’t sugarcoat it; some of these parental strategies are themselves harmful. (There’s no doubt that children are often victims of their parents as well as of carceral systems!) Nevertheless, I think that we as abolitionists can learn from some of the experiments that parents and caregivers perform every day in dealing with problems and tribulations.

In parenting, as in abolition, since no all-powerful, external force is going to come in and save us, we’ve got to struggle, try, fail, and learn, using a combination of imagination, trial and error, and practice, practice, practice. As Ruth Wilson Gilmore says, “practice makes different.” Creativity is key. Mistakes are inevitable — and indispensable. What works today may not work tomorrow. We dream, we plan, we ditch our plans, we do, we undo, we dream and do again.

Maya Schenwar is the co-editor with Kim Wilson of “We Grow the World Together: Parenting Toward Abolition,” the co-author “Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms” and the author of “Locked Down, Locked Out.” She is director of the Truthout Center for Grassroots Journalism. Schenwar has also co-founded organizations including the Movement Media Alliance and the Chicago Community Bond Fund, and she organizes with Love & Protect, a collective that supports criminalized survivors of violence.