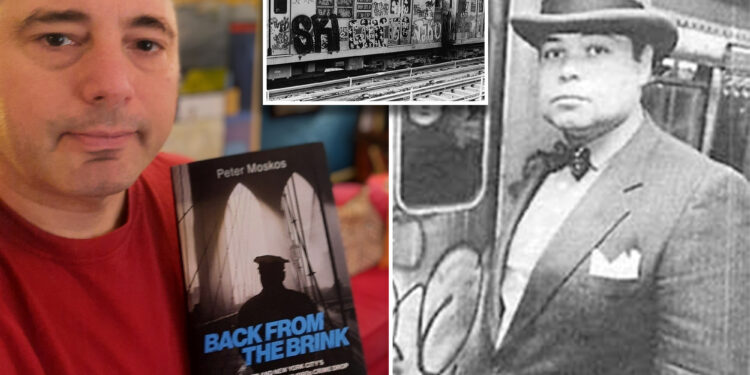

“Back from the Brink,” Peter Moskos’ new book chronicling New York City’s remarkable 1990s crime drop, revives something largely absent from national discourse in recent years: the voice of cops.

It packs a powerful — and desperately timely — message for New Yorkers in 2025: Don’t believe the “experts” and academics who tell you police don’t reduce crime.

Indeed, as we careen toward June’s mayoral primary, public safety remains Gothamites’ top concern. Yet many candidates still advocate what the 1990s turnaround debunked, as Moskos writes: “the dominant sociological ‘root cause’ concept of crime, dismissive of any positive role of policing.”

Moskos critically reminds us social issues like “job creation, income maintenance, medical care, housing, education, drugs, and firearms” did not change majorly in the 1990s — “in fact, poverty increased.”

Yet the Big Apple slashed its murder rate by 20% for five consecutive years, beginning in 1994, even while the city’s “jail population began a decades-long decline in 1992.”

How? Not through introducing an army of social-service “alternatives” to policing and prosecution, as socialist Zohran Mamdani and a rainbow of other Democratic candidates advocate.

Instead, police leaders were given support “to try new ideas” and a fresh policing philosophy was adopted, “one focused on reducing crime, fear of crime, and disorder.”

The book’s genius is in providing a veritable oral history (recounted in cop-ese) of this experimentation and revolution from the inside.

It moves chronologically from the chaos of the city’s gritty, violent 1970s and 1980s to the restored order of the early 2000s, the transformation unfolding through interviews with police officers — and a handful of other key players — who witnessed it firsthand.

That compelling, on-the-ground format is no surprise coming from Moskos, a sociologist who became a Baltimore Police Department beat cop as research for his Harvard doctorate. His first book, “Cop in the Hood,” drew on that experience to illuminate the realities of narcotics enforcement in some of America’s toughest neighborhoods.

The voices in “Back from the Brink” ring with authenticity.

Many interviewees begin by describing how they grew up and what led them to join the NYPD, offering a wide spectrum of backgrounds and motivations. Whether raised in families of addicts or professors, each officer brings a distinct perspective — and a personal stake — in the work of protecting the city.

The story opens in the 1970s NYPD disarray, when mass layoffs fostered officers’ deep resentment and a sense of betrayal.

As the city staggered through the crime-plagued 1980s and into the early 1990s, crises like the crack epidemic and the Crown Heights riot exposed the department’s lack of a clear understanding of the challenges it faced and an effective strategy for addressing them.

But big changes were brewing; the chaos underground proved a powerful motivator.

“Vigilante” straphanger Bernie Goetz in 1984 shot four black teens who’d asked him for money — thrusting the extremes of subway crime and rider fear into the national spotlight.

Surveys showed beggars had intimidated nearly two-thirds of passengers into giving money, and close to 1,000 homeless people were living in the subway system. As then-NYC Transit Authority President David Gunn put it: “It’s really important on our agenda that we continue to create the impression that someone is in control down there.”

Moskos recounts the NYCTA issuing a 1989 code of conduct that now reads like a Karen’s checklist — but starkly illustrates just how unruly the subway had become. Pamphlets like “Introducing Operations Enforcement” announced the agency’s new mission: to “restore a safe, civil environment.”

This drive became part of a broader revolution: basing public-safety goals on not arrest numbers but restoring everyday citizens’ sense of safety.

Vincent Del Castillo, who served as transit police chief during the campaign to rid the subways of graffiti, recalls Gunn wanted more than arrests — he wanted visible results.

“Eventually we got the message,” Del Castillo said. “That began a policy where no train would go into service if it had any graffiti at all.”

Police creativity played a crucial role — such as coating freshly cleaned trains in hot wax, allowing graffiti to be quickly steamed off. Many graffiti artists, frustrated by seeing their elaborate work melted away almost instantly, eventually gave up.

That kind of imaginative policing is a central theme of Moskos’ book.

No one embodied it more vividly than the gritty and flamboyant Jack Maple, a senior NYPD executive under Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s first police commissioner, William Bratton. (Bratton would return as Gotham’s top cop during Mayor Bill de Blasio’s first term; Maple died in 2001.)

Known for his Homburg hats, spats and relentless dedication, Maple recruited what he called “Jack’s broken toys” — officers willing to go undercover as prostitutes or billionaires to catch criminals in the act.

Maple sketched his four-step crime-control strategy on a napkin over drinks at a legendary restaurant. “I’m sitting in Elaine’s,” he once told Moskos, “and you know when you have just enough to drink, you can concentrate on one thing?”

He jotted down his keys to reducing crime: timely, accurate intelligence; rapid deployment; effective tactics; and follow-up.

Backed by other unconventional thinkers in the department, his formula became the foundation for NYPD’s CompStat crime-tracking system — now a global model for data-driven policing.

Maple — like many of the book’s figures — underscores a vital truth: Real progress often comes from those on the ground who observe problems firsthand and have the creativity and drive to solve them.

Many interviewees reference George Kelling and James Q. Wilson’s landmark 1982 Atlantic article, “Broken Windows,” which famously argued visible signs of disorder — like broken windows, graffiti and public intoxication — create an environment of neglect that invites more serious crime.

The core insight was behavioral: When minor infractions go unchecked, both criminals and residents begin to assume no one is in charge.

Grounded in fieldwork and frontline observations, the revolutionary essay became a cornerstone of New York’s 1990s crime turnaround after Bratton operationalized the theory into a citywide strategy.

Under his leadership, police began cracking down on quality-of-life offenses — fare evasion, public drinking, aggressive panhandling and vandalism, among others — on the theory restoring order would deter more serious crime.

Businessman and civic leader Daniel Biederman, who transformed Midtown’s Bryant Park from a dangerous no-go zone into a celebrated urban oasis, told his wife on the drive home from a New Hampshire mountain-climbing trip: “I just read something so incredible and so on target for New York City.”

He applied the theory to park management by establishing clear behavioral standards: “There are seven things I don’t want going on here. This is my version of Broken Windows.”

His list: loud radios, public spitting or cursing, harassing women, smoking, feeding pigeons and letting kids sit on balustrades (they fall and bonk their heads!).

Simply having guards enforce the rules proved so effective, the park hasn’t needed its own dedicated police. “Unless it’s dastardly, nobody gets arrested ever,” Biederman says.

“Back from the Brink” recounts other small but effective interventions — like piping in classical music at the Port Authority Bus Terminal — that helped restore order and drive out chronic loiterers.

Fittingly, the book’s launch took place at a Queens dive bar, where the redheaded tapster spoke in a thick Irish brogue.

Moskos opened the evening with a moment of silence for late key players in New York’s revival — figures like George Kelling and Jack Maple.

“Back from the Brink” is a remarkable tribute. It shows how unconventional thinkers, novel ideas, a few drinks and a lot of grit can produce real, lasting progress.

Hannah E. Meyers is a fellow and the director of policing and public safety at the Manhattan Institute.