Cleveland police searched Black people more than three times as often as White people during stops in 2023 — despite finding contraband at similar rates, a Marshall Project – Cleveland and WEWS News 5 analysis found.

The analysis examined the race of people stopped by Cleveland officers and was developed using data the city was required to provide under a consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice in 2015, following years of excessive force complaints and paying millions of dollars in lawsuit settlements and judgments for police misconduct.

Using records of nearly 17,000 police encounters, the analysis shows officers often used low-level offenses like broken tail lights or tinted windows to search Black people, who were stopped overall at twice the rate of White people.

Black Clevelanders have had a simmering distrust of police that first emerged in the 1960s with the Hough Riots. The city has experienced several high-profile, fatal encounters involving White officers in the past decade, leading to the federal intervention and oversight.

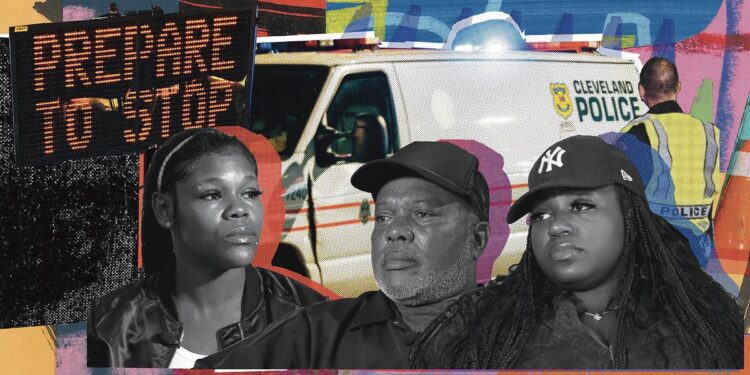

More than a dozen Black people told The Marshall Project – Cleveland and WEWS News 5 that they believed police targeted them for minor violations to look for larger crimes.

“It has something to do with the color of our skin,” said Vanika Burks, who was stopped four times in 2023. “I can’t see it any other way. I should get treated just the way everybody else should.”

The consent decree created a blueprint for Cleveland police to repair community relationships and overhaul its use-of-force policies. It also required the police to record detailed information on every stop.

The news outlets analyzed nearly 17,000 encounters, defined by Cleveland Division of Police policy as any interaction between officers and people stopped for traffic violations or suspected criminal activity.

Black people accounted for nearly 63% of the encounters and were searched at least three times more than White individuals. But when it came to finding illegal items during those searches, contraband was recovered 37% of the time from Black people versus 32% from White individuals.

Stops for low-level infractions have long been the common driver of police-citizen encounters. But stops for minor infractions across the country have led to numerous deadly encounters after escalating into violent and sometimes fatal struggles.

Pretextual stops, the practice of enforcing minor infractions with the intent to look for more serious offenses, have been criticized but have withstood constitutional challenges.

Civil rights advocates and legal scholars say the practice gives too much power to police, often leading to racial profiling while fomenting community distrust.

Jeffrey A. Fagan, a Columbia Law School professor, has studied police reforms and consent decrees for decades. He reviewed the 2023 Cleveland police data at the request of The Marshall Project – Cleveland and WEWS News 5.

Who gets pulled over in Cleveland? Who gets searched? A News 5/Marshall Project investigation.

If officers are searching Black residents more often than White people and not finding a disproportionately greater level of contraband, “that suggests they’re exercising some kind of racial discrimination,” Fagan said.

“They’re using race as a pretext for making a stop,” he said. “The practice itself is leading to disparities which present constitutional problems.”

Mayor Justin M. Bibb said it’s too early to draw conclusions from the data until federal monitors offer their analysis.

“The men and women of our police department are working very hard to keep our streets safe and secure,” he said. “This data is the right first step to be transparent and honest as to where we are. We will confront these truths head-on as a city.”

Council members and the public want more traffic enforcement, he said.

“The residents of Cleveland want a city and police department that will keep our streets safe and secure,” he said. “I don’t care what color you are … we are going to hold you accountable.”

Leigh Anderson, executive director of Cleveland’s Police Accountability Team, leads five employees tasked with measuring the consent decree’s progress and implementing the reforms.

The team is aware of the disparity in the data, but she said it is not evidence of racial discrimination. Updated policies and training now guide how officers conduct stops and searches, Anderson said. She stressed that officers have been trained to not violate any person’s constitutional rights.

The city never collected police encounter data until 2022, when it was required under the consent decree. The city will now use it as a baseline in future years, she said.

“There aren’t any sort of hard and fast rules for how the data should look when it comes to traffic stops and investigatory stops,” Anderson said. “We are figuring out what the data means.”

The city plans to soon turn over its own 100-page analysis of all the encounters in 2022 to the Department of Justice and federal monitors. It will also publish the lengthy report for the public to review. The city will also ask outside experts to review the data for inconsistencies, she said.

“What we’re doing is making sure that bias-free policing is strong throughout” the city, she said.

In a federal court hearing on Sept. 24, consent decree monitors said assessments are underway to review how police handle crisis intervention, use-of force and searches and seizures.

Those assessments, Anderson said, are crucial and will help determine whether police stops are biased or not.

Demographics, including population and race data, and the high volume of complaints in problem areas of the city, must be factored into any breakdown of the data, Anderson said. For example, Black people will likely be stopped more often in neighborhoods with higher numbers of Black residents, she said.

“It’s not the number of stops that’s happening, it’s not the number of arrests,” said Anderson, who has worked on consent decrees in Oakland, California, and Ferguson, Missouri. “Do these officers have biases towards residents?”

Consent decrees are the federal government’s most powerful tool to force cities with histories of abusive policing to change their ways. They’ve been used dozens of times across the country, with oversight often extending more than a decade.

Cleveland came under federal oversight after it made national headlines when officers shot Timothy Russell and Malissa Williams 137 times during a car chase in 2012 and an officer shot 12-year-old Tamir Rice as he played with a toy gun outside a city rec center in 2014.

Cleveland has since enacted dozens of policy changes including use-of-force procedures, enhanced training, internal investigations and de-escalating situations involving mental health and substance abuse.

The federal oversight, including legal fees paid to monitors, has so far cost Cleveland over $60 million.

A recent semi-annual report from federal monitors says the city made numerous strides in recent months.

Andrew Gasiewski, president of the Cleveland Police Patrolmen’s Association, said officers are not searching or stopping people based on skin color. He said officers treat people with respect and are under heavy scrutiny with body-worn cameras.

“The men and women on the streets are doing their job,” said Gasiewski, who spent 16 years making thousands of stops as a motorcycle officer in the department’s Traffic Unit. “They’re taking the training and using it on the street. They’re not out there as this nasty myth to violate anyone’s rights.”

Wayne Drummond, the city’s director of public safety, said supervisor reviews of stop reports and random audits of body-worn cameras are safeguards to make sure that officers are operating within the law. The city has layers of oversight because of the consent decree, he said.

The number of encounters and the racial disparities in The Marshall Project – Cleveland and WEWS News 5 analysis did not alarm him, he said.

“Did the officer conduct those stops constitutionally?” he said. “Were they treating the citizens in those cars in a constitutional manner? That’s my main concern.”

As the national debate continues around these stops, the stop-and-search statistics are often used to gauge the disparate racial impacts of policing in cities with histories of civil rights abuses by police.

More than a dozen drivers stopped and searched by Cleveland officers in 2023 told the news outlets they feared speaking publicly about the encounters. During multiple interviews with drivers who were stopped, themes emerged around tinted windows, fancy cars and police seemingly fishing for illegal contraband in vehicles.

Black drivers accounted for about 75% of the nearly 900 stops for tinted windows, the analysis showed.

Multiple women interviewed said they lower their tinted windows when they see a police car and constantly fear being pulled over.

Nursing student Asia Barton, 26, remembered the June 2023 day when police stopped her for speeding on St. Clair Avenue inside her 2015 Chevrolet Impala — with tinted windows.

Barton said she believes police target cars with tinted windows or fancy rims as a way to find drugs or guns. She has now changed her driving habits and lowers the windows to allow the officer to see she is a woman, believing her gender makes her less likely to be stopped.

In stops for tinted windows in 2023, police searched seven Black women. But they searched 137 Black men, finding marijuana or nothing else about two-thirds of the time.

“If they see that I’m a young Black woman in the car, they’re not going to bother me. That’s crazy,” Barton said. “If they see a Black male with the windows rolled down or rolled up, I feel like they’re still going to get behind them and pull them over. That’s just what I believe.”

Cornelius Love, a 65-year-old East Side retiree, recalled the day he bought a used Volvo convertible and headed down St. Clair Avenue to get an emissions test.

He said he doesn’t believe the Black police officer pulled him over because of his skin color.

But he thinks the stop had more to do with a pricey car in a high-crime area. The officer cited him for not having license plates, driving an unsafe vehicle and for not wearing a seatbelt, court records show.

“They’re looking at fishing for something to stop you,” Love said. “It’s all about money. Whether you’re right or wrong, you’re still going to pay. I’m basically targeted for being a hard-working person.”

Police stopped more than 1,400 people at least twice in 2023, including about 250 who were stopped three or more times, records show.

Burks, 35, who works as a certified nursing assistant, said three of her police encounters in 2023 involved an expired plate or speeding. The fourth stop, records show, was impeding an intersection — but Burks disputes that.

Burks said she gets “paranoid” when she sees a police car on the road.

“When I see one, it makes me stiffen up; I just got to watch it,” Burks said. “It’s hard for me to pay attention. I can’t even focus on the road because they’ve pulled me over so many times. I don’t even really like driving anymore.”

Mario Cage sees it differently. Officers stopped him four times in 2023. He said he doesn’t believe police targeted him for his skin color, tinted windows or fancy car.

“Anytime I got stopped, it was on me,” Cage said. “I have a heavy foot.”

San Francisco, Chicago and Memphis have worked to ban the low-level stops, according to news reports.

A new California law requires police to tell motorists why they are being stopped before asking any questions.

After the Los Angeles Times analyzed traffic stop data in 2019, the city’s police commission created a new policy requiring officers to record their reasoning on body cameras before making the low-level stops.

The number of pretextual stops dropped months later, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Fagan, the Columbia law school professor, said Cleveland leaders should take the news outlets’ data analysis seriously as they work to reform the department and end the federal oversight.

Fagan called the contraband hit rates — police searched Black people nearly four times more often than they found illegal items on them or in their vehicles — problematic, because police are disproportionately stopping black drivers and “exercising some form of racial discrimination” when trying to find illegal items.

“It’s a public safety problem and a disservice to both the White community and the Black community over stopping and burdening black drivers,” Fagan said.

The racial imbalance tells more about the police department’s failure to regulate and monitor what officers do on the streets, Fagan said, adding that it alienates the Black community.

He said police brass should be asking officers a simple question:

“Why are you stopping so many people with such a low payoff? You’re wasting the public’s money, and you’re placing a burden on the people who are stopped.”