Use this reporting recipe to investigate the issue of banned books in prisons.

Our work is only possible thanks to engagement from people close to or affected by book censorship in prisons. As you work through this recipe, if you have any feedback, questions or suggestions, please reach out to the banned book team via [email protected].

I want to…

Know why the issue of banned books in prisons matters

Book bans are a hot-button issue, with controversies erupting in public schools and libraries around the country. But even more restricted reading environments exist all over the U.S. — in prisons and jails, where incarcerated people’s access to books is already restricted.

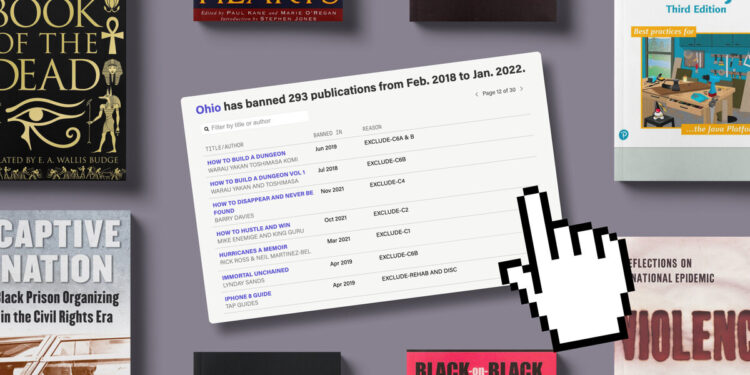

About half the states’ corrections departments in the U.S. told The Marshall Project they keep prison book ban lists, which contain more than 50,000 titles of books facilities don’t want incarcerated people to read. Sometimes books are banned because the state believes they are too violent, sexual or pose a security threat.

This topic is another glimpse into what happens behind prison walls, emphasizing challenges incarcerated people face in accessing and holding onto books they could learn from.

The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering criminal justice in the United States, has published a searchable database with banned book lists from 19 states, including Ohio, along with policy summaries from over 30 states, and takeaways from their publication policy analysis.

See how to request book ban records from state prison systems

📝 Download a sample records request

Former Marshall Project reporter Keri Blakinger requested banned book lists and publication policies from state departments of correction across the United States, including the federal system, to kick off our reporting on prison censorship.

She used two tactics to start:

-

Directly contacting the state’s department of corrections’ Public Information Officer (PIO) and requesting guidance on submitting a request for the policy and for the banned book lists

-

Then, filing each state’s equivalent of a Freedom of Information Act request

Blakinger recommends contacting the corrections department’s PIO to determine the best way to shape the information request. In a few instances, the PIO sent her the policy and banned book list without her needing to submit a formal request.

It is not always obvious where requests for data and documents should go. Some states had data portals, but they were often unclear and difficult to navigate. In other cases, there was just an email address specifically for requests.

Blakinger also recommends sending separate requests (one for the policy and one for the list) because the policy is often easy to find, and will be held up while the list is tracked down and prepared. She learned that there are sometimes two kinds of lists: a list of books coming from outside vendors or senders, and a list of books banned from the prison library. You should specify which one you want in your request.

The lists sometimes contain codes corresponding to the reason for the ban. When you talk to the PIO, ask if that’s the case in your state and request a data dictionary or key to decipher the codes. The format of the list should be a CSV or an Excel doc, whenever possible. Not a PDF. Those are often hard to parse and interpret.

There are states with no lists. These states must, however, document the receipt and adjudication of each book. So, another path is to request the rejection documents themselves. Some states won’t turn them over because they are about specific incarcerated people. Some will. These documents tend to contain the most instructive information about the reasoning behind a rejection.

Get tips to pitch stories and start reporting

Policies pertaining to book bans vary by state — and can even vary down to the facility level.

We spoke with books-to-prison programs, people who are formerly incarcerated, prison librarians, librarians working at the national and international level on issues of prisoner rights to information, and prison educators. Their proximity to the issue helped us identify local and national trends, and understand how fragmented and localized censorship is in prison.

Potential questions and angles:

-

Banned book lists revealing contradictions or biases. For example, the state might allow “Mein Kampf,” but reject books about Black prisoner rights movements, like Ohio.

-

Are people sending books to prisons experiencing confusing and unpredictable bureaucracy?

-

Does the state’s department of corrections keep a banned book list? If not, what is their system for tracking rejected books? Is it decided at the facility level? Does it lead to unfair decisions?

-

Are incarcerated people or prison education programs having their books confiscated after the books are allowed into the facilities?

-

Are religious texts, like Wicca books, being rejected?

-

Are there any facility-level policies that limit the books a person can possess that aren’t in the statewide policy? For example, a facility might limit the books an incarcerated person can possess to what fits inside a shoe cubby, even though the state policy specifies a quantity.

-

What are the rules and procedures around censorship for incarcerated youth, women, or other incarcerated populations, and do they differ from the population of adult men in unintuitive ways?

-

Do book policies limit educational opportunities for incarcerated people that could support their reentry process? For example, coding books are banned in some states, limiting opportunities for employment in tech after release.

-

How are non-English speakers accessing reading materials, and how does their experience vary from the English-speaking population?

-

Who is disproportionately affected by book ban policies? For example, are bans related to sex education hindering access to information about reproductive health for incarcerated women or LGBTQ+ people?

-

Have there been changes to policy that make it harder for loved ones or books-to-prison programs to send books to people on the inside?

-

Are there mailroom issues like mail scanning and staffing that cause problems for book senders, especially as some states grapple with a staffing crisis?

We put together a pitch template to help you get a conversation started with your editor. You should personalize it for your newsroom as much as you need.

Download and understand the data

We currently have banned book lists from 23 states, and published 19 of them in our searchable database. You can download the lists from our Observable notebook, which also contains policy summaries that we created using ChatGPT-3.5 for 37 states. We explain how we did that here.

The states with banned book lists that we are still working on publishing are: Louisiana, Nebraska, Oregon and Washington. If you are in one of these states and want us to let you know when we have published the data for your states, please email us at [email protected].

This video tutorial walks you through how to download and explore the data using Google Spreadsheets. It also describes some of the limitations of the data.

Quick guide to downloading and exploring the data:

-

To access data for banned books in prisons, visit The Marshall Project’s homepage and search for “Banned Books” using the search button at the top right of the page.

-

Click on the story titled “The Books Banned in Your State’s Prisons.” Scroll down and find the “Download the Data” link in red.

-

This link will take you to an Observable Notebook with banned books lists from 19 individual states and a combined list of all those states. Right-click on the desired dataset, select “Download linked file as,” and save it to a data folder or your desktop.

-

After downloading the dataset, open Google Sheets or your preferred tool to explore the data.

-

If you use Google Sheets, under the File menu, choose “Import” to upload the data.

-

Once the data populates, you can begin exploring banned books in prisons.

Learn about editorial style and standards about reporting on incarcerated people

Media outlets have outsized power over the people we cover. That’s especially true for incarcerated people, who rarely have the agency or power to shape their own narrative. As a leader in covering the U.S. criminal justice system, The Marshall Project offers guidance for characterizing people who are in prison and jail.

If you have used our work and want others to know about it, please share a link or an example with us using this form.

Embed the searchable table with my state’s banned books on my website

Here is code that can be copied and pasted in most web content management systems to display the searchable table of book bans in your state:

If you do not see your state, we might still be processing or securing a list. You can message us at [email protected] to confirm.

You can also learn how to request book ban records from state prison systems.

These examples show the way we framed our reporting and the conversation that it sparked. We recommend that you use these posts as reference points when crafting your own audience strategy, rather than copying the exact language, to best engage and serve your specific audiences.

-

Instagram content — such as a Reel, two carousel posts (1, 2), and Stories — helped us reach a general social audience.

-

On Reddit, we posted in local-based and topics-based subreddits to spark conversation about our work. For example, our post in r/bannedbooks was noticed by a moderator, who then added our tool to the subreddit’s resources page.

-

We also had success on other topic-specific sites, like HackerNews, where programmers and people interested in tech reacted to our story about Ohio’s department of corrections banning coding books and how that might negatively impact the reentry process.

Contact the banned books team

If you have any feedback, questions or suggestions, please reach out to the banned books team via [email protected].

CREDITS

Community Listening & Writing

Vignesh Ramachandran

Andrew Rodriguez Calderón

Ana Méndez

Nicole Funaro

Visual Design

Elan Kiderman Ullendorff

Style & Standards

Ghazala Irshad

Akiba Solomon

Video Tutorial

Jasmyne Ricard

Development

Ryan Murphy

Audience Engagement

Ashley Dye

Editing

David Eads

Andrew Rodriguez Calderón