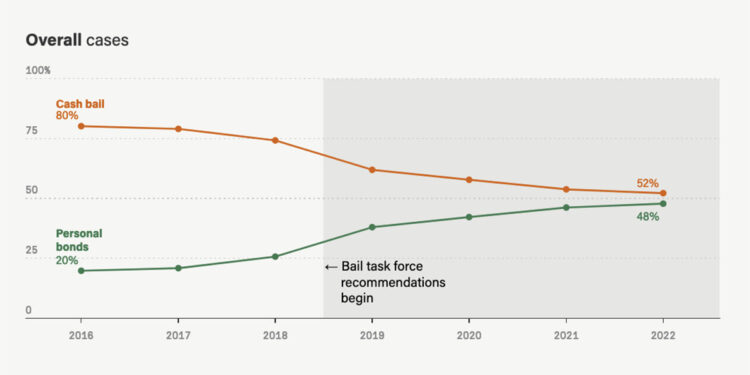

The Marshall Project’s ongoing series about the bail system in Cleveland’s criminal court is based on analyzing data from more than 80,000 cases from 2016 through 2022. We have a record of every bail decision made in these cases, including the date the bail was set, the type of bail, and its monetary value.

The Marshall Project has been scraping criminal case records from the Cuyahoga County Clerk of Courts’ Search Selection and Entry site for about two years, starting in 2021. To analyze bond decisions, we built a database of nearly every case that has gone through the system during our targeted time range.

Only cases that were sealed before our scraper ran are missing from the dataset. We checked all case numbers with the court from January 2016 through December 2021. While we asked for the rest of the case numbers, the court did not respond to our request. Because cases are numbered sequentially, we were able to verify that we have nearly all of the complete dataset.

We shared our findings with court administrators. We incorporated their clarifications (such as statutes considered to be violent crimes) into our analysis and acknowledged their comments in our stories.

In our reporting and analysis, we found that the set of charges against a person accused of a crime brought during indictment was one of the most important factors in a judge’s decision to set a cash bail or not.

In order to compare similar cases with each other, we created two main buckets: those with charges that were exclusively nonviolent and low-level and those with high felony level charges. Felony levels 4 and 5 were considered “low-level” by our definition, since many of our sources noted that these were relatively minor offenses and often the target of reforms.

Ohio maintains a list of statutes that it considers “offenses of violence,” which we used to characterize a charge as being violent or not. Violent offenses were thrown out from the “low-level” bucket. High-level cases contained at least one level 1 or level 2 felony or a violent charge.

In Cuyahoga County, at least two judges touch every case. One judge is responsible for arraigning the defendant, and one is assigned to oversee the case.

To understand judicial behaviors and correctly attribute decisions made to the people who made them, we used the date of arraignment to understand which bond decisions should be attributed to the arraigning judge.

Each case has an associated document in PDF, TIFF or other image formats that contains information about the arraigning judge and the original indictment charges. The text of these documents was obtained using optical character recognition (OCR), and the arraigning judge, original charges and the date of the arraignment were extracted, stored and used for analysis.

All decisions after that were attributed to the final judge assigned to the case.

Cases reassigned to multiple judges after arraignment were thrown out of the analysis, as it was trickier to understand which judge made which decision.

A portion of cases are manually assigned to a final judge, whereas most cases are randomly assigned to a final judge. Manually assigned cases are new criminal charges brought against someone who already has an open case or is on probation. Typically, these cases would be a violation of bail conditions or probation. As such, those cases were handled differently in the analysis.

Docket entries were analyzed to understand when a case was manually assigned versus being randomly assigned. In the docket entry that described the assignment process, either the word “random” or the word “manual” appears, and was categorized as such. Unless indicated, the majority of the analysis focused on randomly assigned cases.

Analysis that focused on arraignment filtered down to the set of cases that had gone through arraignment, which nearly every case that began in 2016 through 2022 had. As such, all cases — closed and open — were included in the arraignment bond analysis.

However, for portions of the analysis that relied on understanding how the final assigned judge eventually behaved during the case, we filtered down to cases where the status had been set to “Case Closed” so that we knew we were analyzing the full set of decisions made in the case.

Out of more than 80,000 cases, less than 10% are marked as open as of Aug. 1. This includes cases that were transferred to a diversion program, as those cases are marked open until the program is completed by the defendant.

For the section about judges who changed the incoming bail set during arraignment, we excluded from the analysis judges who heard fewer than 50 cases in order to have a significant enough sample size to base conclusions on.

Similarly, in the section on the behavior of arraigning judges, we filtered out judges who had arraigned fewer than 100 cases in the six-year time span for the same reasons. This is also why the analysis on arraigning judges is cumulative across all the years, since many judges sat very few times in certain years.