When I used to think of my boarding-school classmate Leon Jacob — before I knew about his convictions, before I learned he was serving a life sentence in a Texas prison — I’d picture him standing in the sunshine outside my dormitory. He was wearing a white polo, so he must’ve been on his way to golf practice. The sun tinged his dark-blond curls. He looked golden, all swagger and confidence as he shouted up for his sister, who lived in my dorm. Because it was the ‘90s, and no one had cell phones to communicate, visitors would usually walk into the dorm and ask a resident to go fetch someone. Leon, however, didn’t bother. He just yelled from the path outside instead, sure that someone would hear him and do what he wanted.

I met Leon in the fall of 1993, when we were new sophomores at Phillips Exeter Academy, a competitive New Hampshire boarding school. I think we were in the same orientation group. I was from Washington state, and so overwhelmed by the formality and traditions of Exeter that I barely spoke. Leon didn’t come from a tony New England background, either. He’d grown up in Houston. But he seemed instantly at ease — tall, with excellent posture, a puffed-out chest, and an easy grin. He made the soccer team and soon traveled in a pack with other sporty, handsome guys wearing white baseball caps backward and smooth-haired girls so sophisticated they knotted silk scarves at their necks.

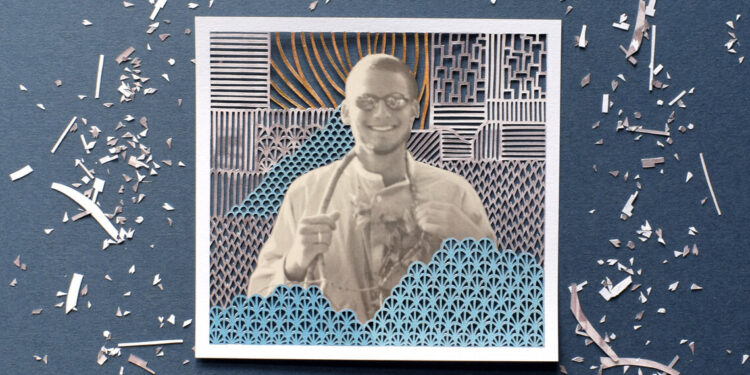

Observing him from under my unfortunate mushroom fringe of bangs, I was bewildered: What made him so confident? Later that year, when I had a class with him, I was even more puzzled. Leon, despite seeming to take the material seriously, often gave answers that showed he was struggling with the concepts — but it didn’t seem to faze him. He was assured about his life plan: He was going to become a surgeon back home in Texas. I figured he’d succeed, even if he wasn’t that bright. I’d see him again at some far-off reunion, no doubt with a pretty wife and poised kids, talking golf and vacation spots as he slapped backs and punched shoulders. His unshakable belief in himself, combined with his good looks, seemed to give him a pass to do whatever he wanted to do.

Then, in 2018, I heard a piece of news so unbelievable I thought at first that I’d dreamed it. Leon, golden Leon, had been convicted of hiring a hit man to carry out the double murder of his ex-girlfriend and his new partner’s ex-husband (the murders weren’t carried out) and had been sentenced to life in prison. I initially assumed something had gone drastically wrong in his life — that he’d had a psychotic break preceding the crime. And although mental illness did play a significant role in his story, as I began to dig into the records and wreckage of Leon’s life, a very different picture emerged that was far more complex — and deeply disturbing.

Leon hadn’t merely succumbed to a single moment of madness. The convictions were the culmination of a yearslong pattern of difficult and often horrifying behavior. He had displayed serious behavior problems, leading to dismissals from four surgical residency programs before he finished his training. (He never did get licensed as a surgeon.) He assaulted and stalked his now ex-wife and his ex-girlfriend. Police and court records show incident after incident where he behaved violently, erratically, menacingly.

Using wealth and privilege, including his ability to hire private lawyers, Leon exploited fissures in the criminal justice system: police in one location unaware of past incidents in another; the failure of the authorities to take domestic violence accusations seriously; ignorance about the intersection between mental health and crime. So often, we see the harshness of the criminal justice system affecting people who are poor and without resources; here, it was like a funhouse mirror version, where Leon evaded the system’s severity time after time.

As I struggled to process all of this, I kept thinking back to Leon standing in the sun, and to why he stood out to me even then. For he wasn’t the smartest or the best athlete. He wasn’t the richest or the nicest. His superlative was his manifest sense of self-belief. Despite myriad personal and professional failures, that same self-assured charisma had always propelled Leon — allowing him to befriend or seduce new victims, convince others to give him multiple chances, and commit new crimes. Even while sitting in prison — convicted after days of testimony and based on a mountain of evidence — Leon has inspired a small online fan base of people convinced he should be set free.

Last year, his new lawyers challenged his convictions, arguing that his trial lawyer hadn’t done a good enough job representing him. This spring, a Texas judge recommended that a higher court deny that motion, and on Sept. 6, the higher court rejected the motion. His lawyers are now considering next steps.

What, I wondered, was at the root of the toxic mix of entitlement and charisma that had allowed him to blaze such a destructive path through the lives of others for so long? And how had he been allowed to dodge consequences again and again? Then, watching a video of Leon testifying at his trial — mussing his curls, grinning, seemingly enjoying himself, and challenging the prosecutor as Leon presented his version of events — I recognized the overconfident kid I’d known. And I began to consider an unsettling thought: Leon still appeared to believe in his own self-mythology. After everything, did he not recognize the damage he’d caused?

Before Exeter, Leon, the oldest of three children, had attended Cooper, a private school in the Houston suburbs. His family was well off — his mother was and is a prominent Houston divorce lawyer, while his father was a surgeon. When he was 13, Leon was the only person home when his father collapsed from a heart attack and died. “I think Leon was afraid that he didn’t do everything right and that if he had done things better, that maybe his dad would have survived,” his mother, Golda Jacob, later testified at his 2018 sentencing. A friend of Leon’s from Cooper described it this way: “I felt like he always aspired to be his father, and then he had to come into being the father of the family very young.”

Two years after his father’s death, Leon started at Exeter. As I talked to schoolmates, two things everyone seemed to remember about Leon were where he was from (Houston) and what he wanted to be (a surgeon). A check of yearbooks showed he played varsity soccer and golf. Yet people from our ‘96 class, who I thought he was close with, said no, he was friends with the sporty guys from ’95. When I called those guys, they said they didn’t know him well either. As Rick Bennett, who was in the year below us, put it: “He was everywhere but nowhere; he seemed to be in with everybody, but not close to anybody.”

Leon’s upbeat presentation struck some as unusual to the point of disbelief. “All of us had our emo moments at Exeter, our depressive moments, and he seemed to be — no matter what was going on — chipper and happy and psyched to see everyone,” Bennett said. “The generous description of that was he was hyper-friendly and eager to please; the negative take on that, and I don’t know if that’s just me projecting now, is he seemed like a try-hard, really desperately wanted to be part of everything.”

Some people who shared his dorm, which was called Browning, remember Leon being more confrontational. An athletic six-foot-one, he “liked intimidating and scaring the shit out of guys, and he would just harass people — if someone’s in with a girlfriend in the front room, he’d find a way to embarrass them,” said one dormmate, who requested anonymity because he did not want further involvement with Leon.

However, another dormmate, Charles Olmsted, recalled Leon “sticking up for me — I was much smaller — [when I was] being picked on by somebody else. He definitely had a bit of a temper, but mostly he was just kind of clueless.” One dormmate recalled teasing Leon for his flexing in the dorm-bathroom mirrors, and several mentioned the time Leon, talking about a girl from Spain he’d been hitting on, said he’d told her he loved the beaches of Madrid. When someone pointed out that Madrid didn’t have beaches, Leon’s response was, “I’m not good at geometry.”

Olmsted wondered if something more serious than malapropisms was going on. Proofreading one of Leon’s research papers, meant to be the culmination of junior-year history class, Olmsted questioned if Leon had learning difficulties. The paper began with the words “I be leave,” which, said Olmsted, “was kind of shocking for somebody at Exeter. I think everyone knew you didn’t start a history paper with the first person, much less the phonetic misspelling.”

Still, Leon’s self-confidence seemed unshakable. He “stood out as being athletic, academically confident, and attractive as a young man, and I think that trifecta of attributes also made him arrogant,” said classmate Claudia Cruz. It was an era before examinations of privilege became a regular part of the conversation, and while my classmates and I likely realized that race, class, gender, and wealth influenced how people moved through the world, those weren’t factors that those with relative power usually acknowledged or apologized for. For instance, Leon’s sister also wanted to be a doctor, and I watched her work her tail off, while Leon seemed to coast; I took it for granted that she’d have to work harder to make it in the same career as her brother. For Leon seemed to epitomize the belief that the world promised something special to people like him, and he expected the world to deliver on its promise.

Leon’s medical career got off to a rough start, and not long into it, superiors began to question his mental health. After college at the University of Texas at Austin, he headed to St. George’s Medical School in Grenada. Caribbean medical schools often take students whose academic records aren’t good enough to get into U.S. med schools. Leon “definitely had this insecurity about being good enough; the fact that he had to go to St. George’s, and his sister got into medical school in the States, really hurt,” said a medical school friend who asked to remain anonymous.

Early in med school, in 2001, Leon married his college girlfriend, Annie Morrison, who was about to start law school in New York. “He was very brash, very in-your-face, had a very big personality,” she testified at his sentencing in 2018. Although they had occasional screaming fights — during college, he’d thrown her clothes off his apartment balcony — he had a real sense of fun, she said. “Leon was very spontaneous. We had a good time together. It was also volatile,” Annie testified, but he was the type of person that some people “really warmed up quickly to and loved.” He’d pay for drinks or dinner, or invite friends to his family’s Vail condo, or have them to his mother’s Houston house for holiday parties, where a professional pianist played tunes and friends were encouraged to pick out rare bottles from the wine cellar. At med school, though classmates suspected his grades were low, “he would go and persuade professors to give him another shot. He really had a way of working things out and getting what he wanted,” the med school friend remembered.

After graduating from St. George’s in 2005, Leon started his surgical residency at St. Vincent’s, then a Manhattan hospital. It’s uncommon, and considered a black mark, for a student not to finish his residency where he started. But the hospital didn’t offer Leon a second year, saying he was “functionally unreliable” and a “potential threat to patients,” according to performance reviews later excerpted in court documents. He landed another residency, at Baylor in Houston, but was dismissed from that, too, according to Annie’s testimony. He went on to yet a third residency, at the University of Texas at Houston. Erika Sato, a fellow resident, became friendly with him there, she told me. He was outgoing and generous about swapping schedules, even when he had a new baby. (He and Annie had their first child in 2009.)

While he developed a reputation for bragging, his outlandish boasts sometimes proved true. Everyone scoffed at his claim that he worked as a model. But then he showed off a Konica Minolta print ad in which he was featured. “He would come out of the OR and say, oh, he did this, that, and the other in there,” Sato said. She figured he’d learned different skills at his other programs. Then he was fired from that UT residency — his third dismissal — for, among other things, talking to students about his penis size and about visiting prostitutes in Mexico, lying about participating in procedures, and asking a chief resident to make out, according to court documents.

Even with that track record, Leon managed to get fellowships at Houston hospitals. Then, in the summer of 2010, Leon landed an unheard-of fourth residency, at an Ohio hospital called Northside.

His evaluations at Northside were scathing. A month into working there, he was given an evaluation stating that he didn’t meet standards for “respectful, altruistic, ethical” skills. The report cited examples of his abandoning a patient who was supposed to be re-intubated, flouting instructions, and lying. A superior asked that he get a psychiatric evaluation; Leon refused, according to a subsequent lawsuit. During a hernia repair, “I directed Dr. Jacob to not push on it with a finger, and I could not stop him before he pushed his finger into it, and we perforated the bowel,” a supervising surgeon later said in a deposition.

Leon skipped meetings and lectures, saying he already knew the material. Nurses complained about his “loss of emotional control.” His score on a standardized multiple-choice test measuring knowledge of surgery was in the seventh percentile. In February 2011, he was asked to resign, but apparently wouldn’t.

His superiors put him on probation, with conditions including “Be TRUTHFUL in ALL communications.” Yet Leon, on probation, lied about the condition of a patient he’d examined and didn’t “know at least basic anatomy” during a carotid-artery surgery, the hospital said in a court filing. In March 2011, Northside fired him.

Pause here for a second. Put yourself in Leon’s place. You’ve struggled in med school. Your test score is in the seventh percentile. You’ve gotten kicked out of four residency programs. It’s time for a reckoning and a new career, right?

Not for Leon. He sued the residency program so it would let him back in.

But Leon lost the lawsuit against Northside — and he lost his appeal on that lawsuit. The termination stood. He wasn’t going to become a surgeon, not through this route. That didn’t stop him from, as time went on, wearing scrubs, telling people he was a surgeon, writing the same in a line-of-credit application, or establishing a practice that supposedly offered “Services in: Transplantation Surgery (Heart, Kidney, Pancreas),” according to Leon’s LinkedIn page.

I go back to my initial take on Leon, and I revise it. He expected that the world would deliver on its early promise to him — and began crossing ethical, moral, and legal lines to ensure that it happened.

Tracing his history, I couldn’t help but be struck by the alarming number of missed opportunities there had been to stop Leon along the way. There were all those incidents on the job. He racked up debts. More seriously, he piled up complaints and arrests for domestic abuse, stalking, assault, and other violent acts. Yet each time, he skated by. Often he moved, allowing himself to avoid the police — and outrun his record — in previous jurisdictions. He declared bankruptcy, wiping his financial slate clean. He used private lawyers to get charges pled down or dismissed or to attempt to seal them. He violated multiple orders of protection with little consequence.

Leon’s ability to elude justice for so long exposes a hard reality about the logistical gaps in our diffuse justice system. Local law enforcement often doesn’t share information across jurisdictions, and Leon moved frequently. Unless they knew where to look, police in one town didn’t know what Leon had done in another place. The FBI maintains central databases of criminal histories for serious crimes, which law-enforcement officers can check. But they don’t always check. And lesser crimes, or information about arrests that don’t result in convictions, are generally not included in the data. While officers can enter information about an order of protection into a central database, the National Crime Information Center, that requires pages of clunky data entry, which few officers have the time or energy for. “As a general rule, if there is a conviction, and it’s on the NCIC, other jurisdictions can see it but don’t necessarily check,” said Joan Meier, a professor and the director of the National Family Violence Law Center at George Washington University. “If it’s just an arrest or a report, there’s almost no chance that another jurisdiction will see it.”

Mental illness clearly factored into Leon’s behavior, but his psychiatric record was presumably unavailable to law enforcement (as almost all medical records are). His family sent him to an in-patient psychiatric hospital, the Menninger Clinic in Houston, in 2013. He was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, and mania, with doctors prescribing lithium for the latter. He “was identified as aggressive, overbearing, and exerting intense interpersonal pressure in an attempt to control the outcome of an interaction,” one of his lawyers wrote last year in a filing arguing that Jacob was being unlawfully detained.

But he spent only two months at Menninger, and walked out to live on his own. He almost immediately began threatening and harassing people again. At trial, against his lawyer’s advice, Leon refused to let his psychiatric records in, and wouldn’t agree to be evaluated by a psychologist, his lawyer told the judge.

Privilege also played a big role in Leon’s ability to miraculously earn chance after chance: He was protected from serious consequences in part because he and his family had the resources to hire private lawyers. Defendants with private lawyers are more likely to be out on bail before trial and less likely to receive prison sentences than those with public defenders or assigned counsel, government statistics show. Prisoners who have private lawyers for their cases are more likely to be White and employed, and usually have a higher income and more formal education than those using publicly funded lawyers. And whatever kind of lawyers they use, White men and people with a college education, like Leon, tend to receive shorter sentences than other defendants, according to sentencing statistics. On top of that, Leon’s family, and in particular his mother, the family law attorney, could presumably navigate the often-baffling court system, given her first-hand familiarity with it. Indeed, called to testify for Leon’s defense at his trial, his mother had to interrupt a different case she was trying on another floor of the same Houston courthouse.

Leon seemed to recognize this, for when he got into trouble, he emphasized his power, his status, and his money. Arrested for threatening and violent behavior in 2012, he “told officers they were making a big mistake and that he would be suing,” directed police on “how to do their job,” and, waiting in jail, said “that he should not have to wait because he is a doctor,” according to police reports. Five years later, after an ex-girlfriend brought an assault case against him, he texted his mother about her: “Please put this bitch in her place.” As he told an undercover law enforcement officer, “My survival is more important.”

Annie Morrison — who had become Annie Jacob, Leon’s wife — felt trapped. Her charming college boyfriend had turned into a violent husband — hitting, grabbing, and bruising her for years, she testified at his sentencing. And the assaults increased after she had their first child in 2009. If she left him, Leon told her, he would find her, take their child, and “kill me,” she testified at Leon’s sentencing. “He said that nobody would ever find my body because he was a doctor, and he had access to chemicals that would dissolve my body.”

Things got even worse after they moved to Ohio. She had two miscarriages before becoming pregnant with their second child in 2011. When she was pregnant, “we were in the kitchen, and he pushed my face into the counter, he threatened to punch me in the stomach,” she testified. “I remember — I remember bringing my legs up as far as I could toward my chest to try to protect my stomach.”

She didn’t know what to do. “I had access to resources a lot of people don’t have access to,” Annie, who is now remarried and goes by Annie Caruso, told me. She was a lawyer herself, so she understood the legal system, and had supportive parents, for instance. “But when I think about how long it took for me to actually do something about what was happening with Leon, I think part of it was this lack of knowledge.”

A quarter of women and 1 in 9 men undergo severe physical violence or sexual violence or are stalked by an intimate partner, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence. A strong body of research suggests helpful approaches, but local responses remain spotty. Some locales provide victim advocates — Annie eventually worked with one, after moving to Illinois — who help victims understand their options, connect them with counseling, update the police, and even accompany police officers to domestic-violence calls.

Police officers, too, can be trained how to handle domestic-violence incidents. In addition to providing housing options for victims, programs offer interventions for abusers, and outline social and legal consequences they face, in an attempt to puncture the common idea that they won’t be held accountable for the abuse.

Annie felt stranded in Ohio, with few friends and no extended family, and where Leon no longer even had a job. She didn’t confide in anyone for a long time, she told me. “There’s a misunderstanding about how abuse works, the cycle and the psychology of it, the isolation and the fear. And that misunderstanding leads to victim blaming, It’s so common to hear, ‘Why didn’t she leave him?’” she said in an interview. “That creates a lot of shame and embarrassment. I was certainly embarrassed that it was happening to me. And I fell into thinking, I am not the person that this happens to; I am a professional, I can take care of myself, I’m a lawyer and I should know the legal system and the resources available, so no one will believe me and no one will understand why I didn’t leave sooner. And that made it so much harder to reach out and ask for help.”

In the summer of 2012, Annie had their second son. She and Leon separated for three weeks or so, then got back together. They moved about an hour from their Ohio home that fall, to a Pittsburgh suburb; it was closer to Annie’s job as an in-house lawyer at a pharmaceutical firm. While she worked, handled childcare, and paid the bills, Leon “typically would have dinner with us, and then he would leave, and he would be gone again,” sometimes returning by the morning, sometimes not, she testified. He was drinking, playing online poker, and going to Rivers Casino in Pittsburgh, spending tens of thousands of dollars earmarked “for daycare and food and clothing and rent,” Annie testified. That fall, Leon applied for a line of credit at Rivers, writing that his yearly income was $200,000. His occupation, he claimed: “Surgeon.”

Their second child was a few months old when, on Annie’s birthday, she asked to sleep in. Leon lifted up the mattress so she dropped to the floor, then threw the mattress on top of her, she testified. You can sleep there, he said.

A few days later, while Annie got the children ready for daycare, Leon took her keys and cell phone and prevented her from leaving by wrapping himself in a comforter in front of the front door.

Annie, for the first time, called the police.

This is another inflection point where Leon might’ve been stopped, had the police handled it differently. However, as is common in domestic-violence calls, rather than helping Annie, they left her exposed to more violence. When officers arrived, “they talked to both of us together, and Leon was standing there telling them that I was free to leave,” Annie told me. The police apparently believed Leon and didn’t question Annie by herself or offer any resources. They left once Leon gave her back her keys and phone. Annie drove away with their baby, but she’d left their three-year-old son with Leon and, worried, returned to get him.

Annie went up to her and Leon’s bedroom, and Leon and the older son walked in. “And Leon pushed me onto the bed, and he pinned my arms up and put his knees on my elbows so that I couldn’t get up,” she testified. With one knee on each elbow, and the boy watching, he held a razor to her throat. He screamed, “that if I ever called the police again, he would kill me.”

“He told me the only way I was leaving the house was in a body bag,” Annie testified.

She’d finally gotten up the nerve to report Leon — and the official response had endangered her even more. “That’s a common story I hear: People don’t want to reach out to the police because they know they’re likely going to be subjected to additional violence for just making the call,” Annie told me. “Victims are left feeling like they have no way out.”

Annie eventually told her parents about the abuse, contacted a lawyer, and made plans to move to Illinois. She asked her mom to be in town when, in August 2013, she told Leon that she’d set up a solo bank account. He didn’t react that night, but the next morning, as she got the kids ready, Leon wrapped a towel around Annie’s arms and chest and pushed her up the stairs to their laundry room, she testified. He screamed and whipped laundry at her. Then he hurled a toolbox at her; she ducked as it smashed into the wall. She fled the house with their children, and her mother accompanied her to a courthouse, where she filed for a protective order that required Leon to leave the house.

Around this time, in August 2013, Leon’s family in Houston arranged for him to go to Menninger, the psychiatric clinic in Houston. Leon — who had not seen a psychiatrist before, his mother testified at his sentencing — was diagnosed with an array of personality disorders.

Here’s yet another point where Leon might have been stopped, if he’d continued treatment. But he left, and his harassment intensified after Menninger. He called, emailed, and texted Annie — who was now in Illinois — sometimes hundreds of times a day, along with her family and friends, even showing up at the kids’ new school, though he was not allowed there. He threatened to torture her parents in front of her, adding, “You have no clue where I am, you have no clue when I’m coming” in one conversation played in court. Police in Illinois advised her to record Leon’s actions and connected her with a domestic violence victims’ advocate in their department, who accompanied her to court and referred her to a therapist. Police took the case seriously this time, conducting regular safety checks.

In 2014, Illinois charged Leon with 22 felony counts, including stalking, cyberstalking, and intimidation. He was jailed, but was out on bail within a month. Using a private lawyer, he pled down to a single charge of attempted cyberstalking, a misdemeanor, and was given no further jail time.

In 2012, when Annie and Leon moved from Ohio to the Pittsburgh area, it wasn’t only because of Annie’s job and Leon’s unemployment. Annie, pregnant with their second child, knew Leon had also been dating another woman in Ohio, and she wanted to put distance between them and the woman, she testified. Though Annie didn’t then know this part, Leon quickly entangled that woman, her ex-husband, and their children in his net of chaos and rage.

The woman, Patricia Goodin, had been the administrator of the residency program at Northside. Annie and Leon were friendly enough with the Goodins that they’d have dinner with them and their two children. Around 2010 or 2011, Patricia’s then-husband, Darren Goodin, became suspicious that Patricia and Leon were having an affair. He and Patricia divorced soon afterward, he testified at Leon’s sentencing. By 2012, the year after he’d been fired from the residency, Leon regularly spent the night at Patricia’s place. “When he would get angry, he would get very angry,” the Goodins’ daughter testified. “He always smelled like alcohol.” (Patricia could not be reached for comment; Darren and their daughter did not respond to a request for comment.)

Darren sounded alarms about Leon’s behavior, to little effect. In the summer of 2012, “he threatened to blow up my house, threatened to kill me,” Darren testified. He said he filed for an order of protection against Leon, but it seemed to have minimal impact. That same summer, Darren called the police after recording Leon saying, “I’ll beat your ass in front of your kids” while Darren had his children in his car. Leon was arrested on that complaint. Once again, he was able to afford to hire a private local lawyer, and the charge was dismissed.

Leon also hit the Goodins’ 98-pound, 14-year-old son. During a custody dispute that summer, Patricia and Leon decided “to, like, stage something, like as if my dad did something. So they decided to punch my brother in the chest,” the daughter testified. Leon hit her brother, a 5’3 ninth-grader, and he “toppled over,” she said. Police questioned the family members, but they offered conflicting versions of events. Later, the son clarified that Leon and his mom had come up with the idea of hitting him, and the boy explained that he no longer lived at his mom’s, so he didn’t have “to fear them finding out and doing something.” With that statement, the police took the case to the local prosecutor, though the prosecutor questioned the witnesses’ credibility and said “there was not sufficient evidence to pursue charges,” the Poland Township, Ohio, police wrote. Leon had skated by once more, even with the alleged victim a minor.

Finally, in late 2012, Leon faced a charge that could have had real consequences: burglary, a felony.

Leon and Patricia’s relationship was already turbulent. In the spring of 2012, a neighbor of Patricia’s called the police, overhearing fighting at her place. Officers found Leon pounding on the front door, yelling, “‘It’s been more than a fucking minute’ and ‘Open the door,’” they wrote. Leon “advised that there was no fight,” the police wrote, and when they couldn’t make contact with the person inside the apartment, they didn’t investigate further.

That December, police again were dispatched to Patricia’s apartment with reports of two people yelling. Leon had broken Patricia’s door and doorframe, but she didn’t want to pursue charges because “Mr. Jacob was going thru a tuff time,” the police wrote. At 1:30 the next morning, Leon called Patricia from a Holiday Inn parking lot, drinking and possibly suicidal, Patricia wrote in a police complaint. She took him to her apartment. Several hours later, she told him to leave, and he did, but when she didn’t answer his texts and calls, he returned. He grabbed the broken door trim “and swung it at my head,” she wrote. She rushed to her car, but he ripped off the car door handle, “sat on my car hood and told me that I wasn’t allowed to leave,” and carved “USER” on the car.

Leon was indicted on a charge of burglary. The case was supposed to go to trial the following summer, with a local private lawyer once again representing him. However, Patricia, who was under indictment in another case, refused to testify, Paul Gains, Mahoning County’s prosecuting attorney, told me.

Leon pled down to trespass, a misdemeanor.

If Leon had committed all these offenses in a single town, the police would likely have been tracking him, on guard against future violence. But the police in Poland Township, Ohio, handled the Patricia Goodin incidents. Darren Goodin’s misdemeanor complaint and order of protection were filed in Struthers, Ohio. The McCandless, Pennsylvania, police responded to Annie’s domestic violence call. Annie’s order of protection was filed in Allegheny County. And her subsequent orders of protection and the stalking and intimidation charges were in Cook County, Illinois. Leon’s on-the-move life made it difficult to assemble a comprehensive record.

In 2014, with the string of incidents involving the Goodins behind him and fresh off the Illinois cyberstalking misdemeanor, Leon, now divorced from Annie, was living in a hotel in Pittsburgh. He became friendly with an employee named Meghan Verikas. Though she was married, “there was an immediate attraction,” Leon testified at his trial. She thought he was a surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, an impression underlined by the fact that he often wore scrubs, she testified. They began dating, and Meghan soon left her husband for Leon, who convinced her to move to Houston with him after just a few months together.

Four years later, he’d be convicted of trying to kill her.

Sitting in the corner booth of an Olive Garden in Houston, Leon faced a problem he hoped to make disappear. It was March 8, 2017, and Meghan, who’d broken up with him two months earlier, had gone to the authorities, who had filed assault and stalking charges against him. She planned on testifying, which, he told a bail bondsman, would “be an embarrassment to me and my family. And my mother is a lawyer here in town, a well-known lawyer, and this would be a great embarrassment,” according to the bondsman’s testimony.

At the Olive Garden, a peppy jazz soundtrack warbling overhead, Leon discussed his options with someone introduced to him as a hit man, according to trial testimony. He was actually an undercover officer named Javier Duran, and the conversation was being recorded by the Houston police. “I need her to leave,” he told Duran. “Go back to Pittsburgh.” Though Leon said he didn’t want her hurt, he also said that Duran could “snag her, put her in her fucking room, and tell her, ‘If you don’t fucking leave, I’m going to kill her parents.’” Leon also discussed injecting Meghan with potassium chloride: “Stop her heart, untraceable.”

“I think you’ll make it very clear that if she doesn’t leave, there are going to be severe consequences,” Leon said.

Meghan had moved to Houston with Leon in late 2014; he’d said “he was going to be a doctor here,” she testified at trial. In Houston, Leon did odd jobs, like working for a family friend’s cookware company or doing projects at Houston Methodist Hospital (his mother was on a hospital-related board with several influential doctors there), while indicating to old friends like Sato that he was employed as a doctor. He went bankrupt in 2016, owing more than $100,000 to seven lawyers in five cities and with debts to courts in Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. His sparse assets included a BMW 550i Sport, jointly owned with his mother, and a monthly plane ticket paid for by his sister. With the bankruptcy, filed for him by a private Houston lawyer — the lawyer’s fee was paid by his mother — his debts were cleared.

Meghan, working at a Houston hotel, paid their rent and bills. Leon testified that he relied on his mother to cover groceries, child support, and his cell phone bill, though, as he told the prosecutor, “It could be considered more like family money.” Asked to explain that, Leon said, “My family is pretty affluent. All of us are professionals. My sister is a surgeon, my brother is an engineer, my mom is a lawyer, I’m a doctor. We all have done, at times in our life, quite well.”

From the start of their relationship, Meghan told me, “I was abused and manipulated.” On the stand at his trial, she described how by 2017, when they’d been living in Houston for more than two years, he would throw things, scream, and threaten to “burn the apartment down” if she left.

She told me: “Similar to other domestic violence survivors, I planned my escape for months. I made a conscious decision after one session of therapy: I could not continue living in fear, and if I stayed, I would most likely end up physically harmed.”

One day in January 2017, Leon “said he didn’t like the way my face was,” Meghan testified. She decided she had to go. He “put his hands over my face” so hard that it left a mark. She ran to her car. Leon was “slamming his fist against the driver’s side window and pulling on the car handle” and threatening to “punch the window in.” She drove to his brother’s house because she was close friends with his brother’s wife, Leslie Jacob. Leslie “saw a handprint. It looked like a thumb indentation and then some fingerprint on her face,” Leslie testified.

Leon tracked Meghan down, banged on Leslie’s door, and “burst in my house,” Leslie testified. Meghan hid in a closet. “‘Where is that fucking bitch?’” Meghan heard him say.

Meghan moved to an unregistered room at the hotel where she worked. Leon called the front desk; he lurked in the valet area. Meghan tried to hide her car, parking it away from her assigned spot at the hotel, and asked people to come with her whenever she left the building for work meetings. Leon used spoofing technology to make it look like he was calling from, say, her brother’s phone number, Meghan testified. He called her brother, her mother, her father. He sent “hundreds of text messages” to Leslie telling her to help get them back together, Leslie testified.

Once, Leon followed Meghan as she drove out of the hotel lot. She called 911, staying on the phone as she drove in circles, hoping an officer could get to her. “As I’m driving, at one point he jumped out in the street in front of my car and started yelling, ‘You’re making a big mistake. You don’t know what you’re losing,’” she testified. On top of the safety concerns and emotional violence, she was trying to handle the logistics of leaving him: Would she get in trouble for breaking her lease? How would she find a new apartment?

Meghan went to the authorities, who filed a misdemeanor assault charge against Leon followed by a stalking charge — a felony. A prosecutor at the Harris County District Attorney’s Office helped Meghan file for an order of protection. Leon was arrested and jailed, but, yet again, he used a private lawyer and money — in this case, $15,000 — to pay the bond and get released. But the cases stood, and Leon had come to believe that, besides preserving his family’s reputation in Houston, he could somehow reinvent his medical career if Meghan were to drop them.

“It was a hindrance,” he told a prosecutor at trial.

He urged his mother to intervene. “Call me asap. I want this girl finished,” he wrote to her on Jan. 18, 2017 about a week after Meghan had left him.

“Stop,” Golda Jacob responded.

“Please put this bitch in her place,” Leon wrote.

“NO!!!!!!!!!” Golda wrote. “I am done u need to take care of your responsibilities and not always let someone else take care of u.” (Golda did not respond to a request for comment.)

Meanwhile, just a few days after Meghan left him, Leon began sleeping with a Houston veterinarian named Valerie McDaniel, he testified. By March, he and Valerie were living together and sharing a bank account. Valerie was recently divorced; Leon’s mother had represented her in the divorce, and Valerie had also been Golda’s next-door neighbor.

Valerie accompanied Leon to the Olive Garden meeting, and she had her own reasons for talking to Javier Duran, the undercover officer. Valerie offered him $10,000 to kill her ex-husband, Mack McDaniel, according to Duran’s testimony.

Duran became involved in the case after the bail bondsman Leon had spoken to alerted police, concerned about Leon’s questions about how to stop Meghan from testifying. “I felt like I was talking to the devil himself,” testified the bondsman, Michael Kubosh. The police arranged for Duran to be introduced to Leon as a “hit man” via an acquaintance.

While Leon said he wanted the case to go away for multiple reasons, he also seemed fixated on what he saw as Meghan’s relative lack of status.

“‘These are just lower-class middle girls from Pittsburgh’? You said that, right?” a prosecutor, Samantha Knecht, asked him at trial.

“Characterizing Meghan and one of her friends,” Leon replied.

“She’s uneducated, never graduated college. I took her out of lower middle class,” he told Duran on a recording.

If before, law enforcement hadn’t done enough to stop Leon, here the police weren’t taking any chances. (Houston police spokespeople did not respond to requests for comment; the Harris County district attorney’s office declined comment.) Duran, who regularly worked on cases of solicitation to commit capital murder, testified that after that first Olive Garden meeting, he felt he had enough evidence to prove that charge against Leon. The police kept building their case, though, recording 12 phone calls in which Leon discussed the plot, plus two in-person meetings between Leon and Duran, in the brief period between that March 8 meeting and just after midnight on March 10. Duran kept pushing Leon on what, exactly, he ought to do to Meghan. He also collected more than $10,000 in payments from Leon.

The police decided to cap the case by having Mack and Meghan photographed as if they’d been murdered and abducted, respectively. The pictures were haunting: Meghan, already the victim of stalking and abuse and scared of Leon, had her wrists zip-tied and her mouth duct-taped and was “hysterical, visibly shaking,” an officer testified. As for Mack, the police poured pig’s blood over him and posed him slumped over the steering wheel of his car, a fake bullet hole in his head. Asked by a prosecutor how hard that was to do, Mack testified, “Beyond unimaginable.” (Mack could not be reached for comment.)

Duran kept Leon updated throughout the day of these supposed crimes, and that night he stopped by Leon and Valerie’s apartment. He spoke to the couple on their balcony, telling them Mack McDaniel had been killed. Valerie then went inside, and Duran repeated the point, telling Leon that Mack was “dead, he’s gone.”

Leon responded, “What are we going to do with the girl?”

“I’m not planning on her coming back alive,” the officer said.

“I already knew that,” Leon said.

Duran left and later texted Leon a photo of Meghan, duct-taped and zip-tied, then called to follow up.

“Yeah, that’s her,” Leon responded. In a subsequent call, Leon told Duran: “She either packs her shit up and goes, or you’re going to have to do what you have to do.”

In a final call, Duran told Leon that he wasn’t able to reason with Meghan about leaving and “she’s dead.”

“You already took care of it?” Leon asked, then said he didn’t want this to “come back to hurt me here.”

Shortly afterward, at Leon and Valerie’s apartment, police arrested the couple.

A few days later, Valerie killed herself, jumping from their seventh-floor apartment.

Leon turned down a plea deal, for 40 years in prison, insisting on going to trial — and on testifying in his own defense. After a mock examination, one of his lawyers warned him about “how badly he was coming across.” Leon’s response, according to the lawyer, as recounted in court papers: “He kind of joked about it, and always told me that he would be fine when the time came.”

When Leon took the stand at trial, he said, “I never asked anybody to kill anybody.” He said he was paying money so the undercover officer would convince Meghan to relocate to Pittsburgh, where she’d presumably drop the Houston cases, and help her set up a new life there. (The allegations involving Annie and the Goodins were not part of this phase of the trial; those witnesses testified at Leon’s sentencing.)

The prosecutor challenged Leon. “Did you not want anybody hurt when you said, ‘Inject her with potassium chloride’?” she asked.

“I said that was something he could do. I didn’t say for him to do that,” Leon responded.

At the end of the four-day trial, Leon was convicted after two hours of jury deliberations. At his sentencing hearing, the prosecutor called Annie, the Goodins, and other witnesses to testify about Leon’s turbulent history; Meghan also testified again. “I find tremendous satisfaction knowing that my tenacity, strength, and perseverance was what inevitably put Leon in prison,” Meghan told me. She credits the Houston-area domestic-violence nonprofit AVDA, where she now volunteers, for helping her with therapy and support as she recovered from the abuse.

The prosecutor also played phone calls that Leon had made from jail. Describing a TV reporter covering his case, Leon said, “I mean, I know [Valerie’s] dead and I have to mourn her, but this one’s cute.” He also said he wanted “Bradley Cooper to play me in the TV movie.”

The jury gave Leon a life sentence. It is “life” only in theory, however — he will be eligible for parole in 2047.

In the final recording Duran made, Leon, between discussing Mack’s death and Meghan’s abduction, offered Duran a drink and boasted about the price of his apartment. When the undercover officer, evidently responding to the view from the balcony, said, “I gotta open up a veterinary clinic,” apparently referring to Valerie’s job, Leon corrected him: “You gotta be a doctor.”

I thought, in researching Leon, that I might find the root cause of his behavior. But a person can unnerve some classmates and charm others and go on to a perfectly ordinary life. The keyed-up, socializing Leon of high school was not predestined to hurt so many people. He made choices. He made terrible choices. And he didn’t have to face consequences until his last days of freedom. It’s hard not to imagine how it might’ve turned out had Leon been stopped earlier, and to ponder the unalterable effect he had on those whose lives he ravaged: Annie, their sons, Meghan, Mack McDaniel, the McDaniels’ child, Darren Goodin, the Goodin children.

After hiring a new lawyer, Leon appealed his conviction on the basis that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to convict him, among other issues. The appeal was denied. Josh Schaffer, a lawyer working on Leon’s current challenge to his conviction, wrote in an email to me that despite the court affirming the jury’s decision, “the issues raised” by that lawyer were “substantial.” Now in prison in Rosharon, Texas, Leon initially agreed to talk to me for this story, but Brian Wice, another new lawyer he’s hired, quashed that.

Last year, Schaffer and Wice filed another challenge to Leon’s conviction, arguing ineffective assistance of counsel concerning one of his original trial lawyers, saying he should’ve pushed Leon to plead guilty or introduced evidence of Leon’s extensive mental health problems to jurors. A judge recommended, in May, that a higher court deny the motion. Earlier this month, Texas’ Court of Criminal Appeals did so; it didn’t offer a written opinion as to why. His lawyers are mulling their next moves. “The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals rejected Dr. Jacobs’ (sic) case without giving meaningful consideration to his weighty legal claims,” Schaffer wrote to me. “Unfortunately, this court has a track record of ignoring controlling law from the United States Supreme Court. Dr. Jacobs (sic) has three months to decide if he wants to appeal to the Supreme Court. His case presents exactly the kind of issues that attract the Supreme Court’s attention.”

And online, Leon has amassed a modest number of supporters: on a Facebook page titled “Justice for Leon Jacob, MD,” which is described as being run by his “bestfriend.” One woman wrote that she believes he was “entrapped,” adding, “STAY STRONG LEON.”

The night Leon met with the undercover officer that last time, a few hours before he was finally arrested, he wore a T-shirt that read, “Trust me. I’m a doctor.” After the police took him into custody, he said, in a statement recorded on video, sounding incredulous, “Me? I don’t know why I’m being arrested.”

Yes, him. His time, finally, had run out.