When I was a kid growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, the name “Unabomber” would frequently come up in adult conversations. Like a distant relative I never met, I would try to imagine his physical appearance and always pictured a man in a long black trench coat clutching a metal suitcase that happened to contain a labyrinth of multicolored wiring on the inside. If it opened, the world would implode into a ball of fire, much like King Koopa from “Mario Brothers” would exhale.

At ten years old, in 1994, I was both terrified and curious. It never occurred to me that my future work would take me down a path where I would receive letters from a convicted domestic terrorist and engage in conversations with him about the current state of the world.

The Unabomber was finally arrested in 1996 and his identity was confirmed after he had planted and sent homemade bombs that killed three people and injured 23 over 18 years. As a kid, I couldn’t make much of it, except that the FBI now possessed the metal suitcase I had fabricated in my mind that could destroy the world. I had no knowledge of the ideologies this man, now known as Ted Kaczynski, possessed, that he believed, “the Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race.”

Beyond playing Nintendo, and in school, “The Oregon Trail,” I did not think much about the modern world or technological advancements.

Many years would pass before I would begin to seriously think about why people commit crimes, especially murder. Even then, in 2012, as I began researching my first true crime book, I didn’t think much about why other people other than my “subject,” Maksim Gelman, committed murder. However, after nearly eight years of conducting interviews in prison, I’d hear a colossal number of stories about what happens behind those walls. As I sat in the visiting room each month, where I’d cross paths with many other incarcerated men, I began to wonder not simply about the crimes they have committed, but why they made those choices.

In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, while isolated at home, I began to seek answers. I created a website, Beyond the Crime, which serves as a platform for people incarcerated for murder to discuss any subject of their choosing in the hopes of gaining a better understanding of the criminal mind and criminal justice system. After sending out a bundle of letters, the responses I received from incarcerated people all over the country were overwhelming.

There were some people I didn’t expect to hear from, and Ted Kaczynski was one of them. When a letter arrived in my mailbox, I stared in surprise at his name which was printed so neatly it could pass for typed font.

By this time, I had a decent amount of knowledge about his case and had read his manifesto, so I was not shocked when his first letter asked for my thoughts on societal issues and hypothetical situations involving the current political climate.

I have always been open-minded and one to believe that anything is possible, no matter how far-fetched, so I played along. In my next letter to him, I considered various outcomes to his proposed outlandish scenarios involving sexual reparations. I also explained why it was unlikely such a thing would ever happen, which he agreed, admitting, “it was a joke with a point.”

Thus, a pen pal friendship was born when he responded a few weeks later complimenting, “The fact that at least one intelligent person—yourself—has taken it seriously shows how far the left has wandered into absurdity.”

For months, we continued to correspond, often discussing topics ranging from political correctness to language to societal issues in America and other cultures. In each letter, we’d exchange ideas centered around many of his assertive observations such as, “We now have a society in which people (and not just those on the left) try to get what they want by making other people feel sorry for them. This isn’t something that happens only in individual instances—it’s a mass phenomenon.”

Eventually, he agreed to a formal interview, giving me permission to share it on Beyond the Crime.

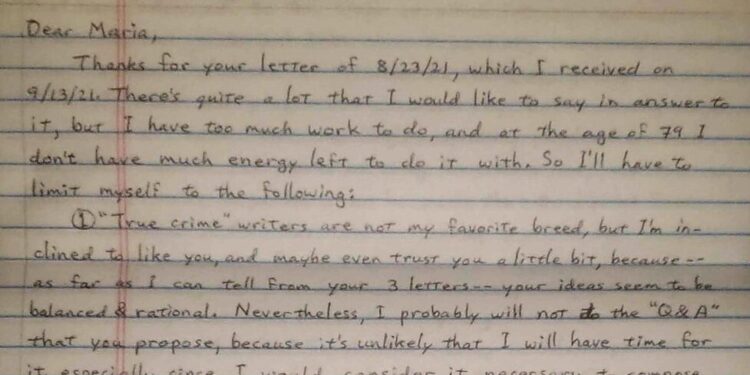

“’ True crime’ writers are not my favorite breed, but I’m inclined to like you, and maybe even trust you a little bit, because—as far as I can tell from your letters—your ideas seem to be balanced and rational…I might have time to answer one or two key questions about the content of my books,” the Harvard-educated Mathematician admitted.

We had planned to discuss his book Technological Slavery, but when I sent him my questions in the late fall of 2021, I was met with silence. Never trusting the prison mail system, I wondered if my letter had been lost, so I followed up with another letter, asking if he had received my questions—more silence.

In the pit of my stomach, I knew something was wrong. In the next letter, I asked if he was okay. By the end of December 2021, news stories had been released, explaining that he had been transferred from the prison in Colorado to Butner, the federal medical center in North Carolina.

A “goodbye” letter followed shortly after I heard the news of his poor health, in which he explained, “I have to apologize for not answering sooner, but I have a good excuse: I’m very sick and may not live long—that’s why I’ve been transferred to the federal prison hospital in North Carolina…whatever time I have left has to be spent on getting some legal matters squared away and (if possible) on finishing up some writing projects. So, I won’t be able to correspond with you any longer.”

He then went on to give me an idea for a future book that he wished I would write and referenced where I could start my research, encouraging, “I expect you’ll find a lot of this material fascinating (even if sometimes horrifying), maybe even fascinating enough so that you’ll want to write about it.”

I’m not sure if I will ever follow up on any of the ideas he has suggested to me. I’m still trying to make sense of my feelings about the 81-year-old’s death by apparent suicide while he was battling cancer in June of this year.

During my correspondence with him, I had started to look forward to his letters. He had permitted me the rare freedom of total self-expression, something that has become uncommon these days. Even if he disagreed with my opinions, he always seemed to remain open-minded enough to consider my ideas and discuss them, and I did the same when it came to his.

Nowadays–even among close friends—open dialogue and listening to what someone has to say without becoming offended seems to have become a dying practice. However, those letters provided a space that felt familiar to old college classrooms I remember sitting in during my time as an undergraduate student where all ideas, no matter how unconventional, seemed to be welcome.

I know many people will find my feelings odd, and may even pass judgment—how can I not only speak kindly of, but actually admit I enjoyed speaking to a murderer?

In my attempt to understand why anyone commits murder, empathy has always driven me forward. With Ted, it was no different. From my perspective, he was a person who had committed some of the worst atrocities, but who I learned was also capable of extending some humanity.

I can’t help but wonder where the two extremities—good and evil—meet and separate. I imagine a line drawn in the sand that becomes erased and redrawn repeatedly upon the realization that it’s impossible to find balance within such vastness. The line drawn will never fully represent equalness on both sides. Isn’t this the quandary of the human heart, or rather, the human conscience?

Really, how could someone who had caused so much destruction and had hurt so many people show me consideration and kindness? I’d like to think this is what it means to be human, but what the media, instead, often labels as “monster” and buries under the heavy weight of sensationalism.

I regret that I was not able to complete my interview with Ted—I know it would have most likely offered more insight into his thoughts and beliefs, which were undoubtedly the catalyst for his criminal actions. However, I am grateful for the experience, nonetheless, of having some access into his mind and ideas— “yours for wild nature”—as he always said in closing each letter to me.