18

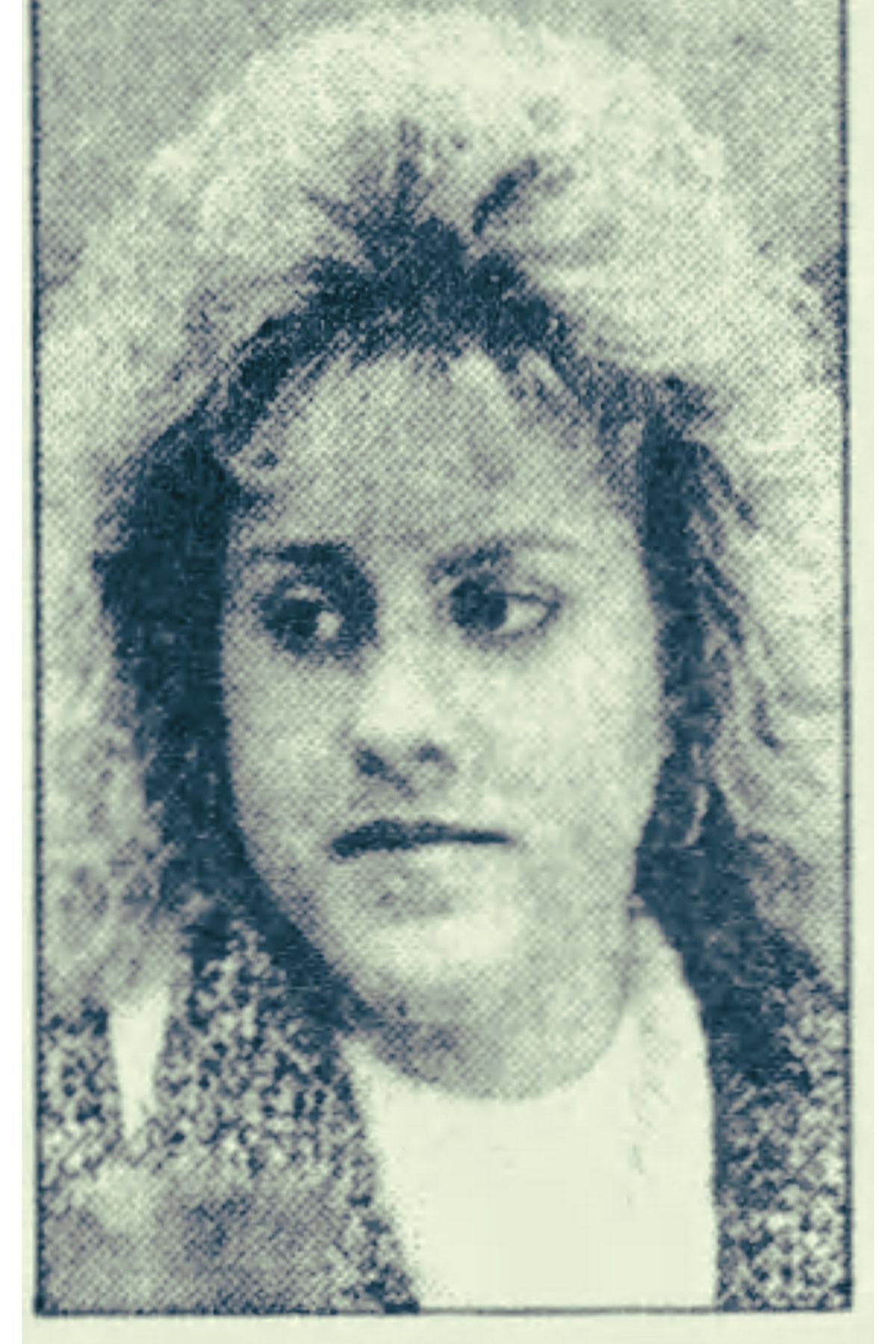

WAUSAU, Wis. — Lisa Anne Cihaski, 21, was an intelligent and beautiful young woman with a handsome boyfriend and a good job.

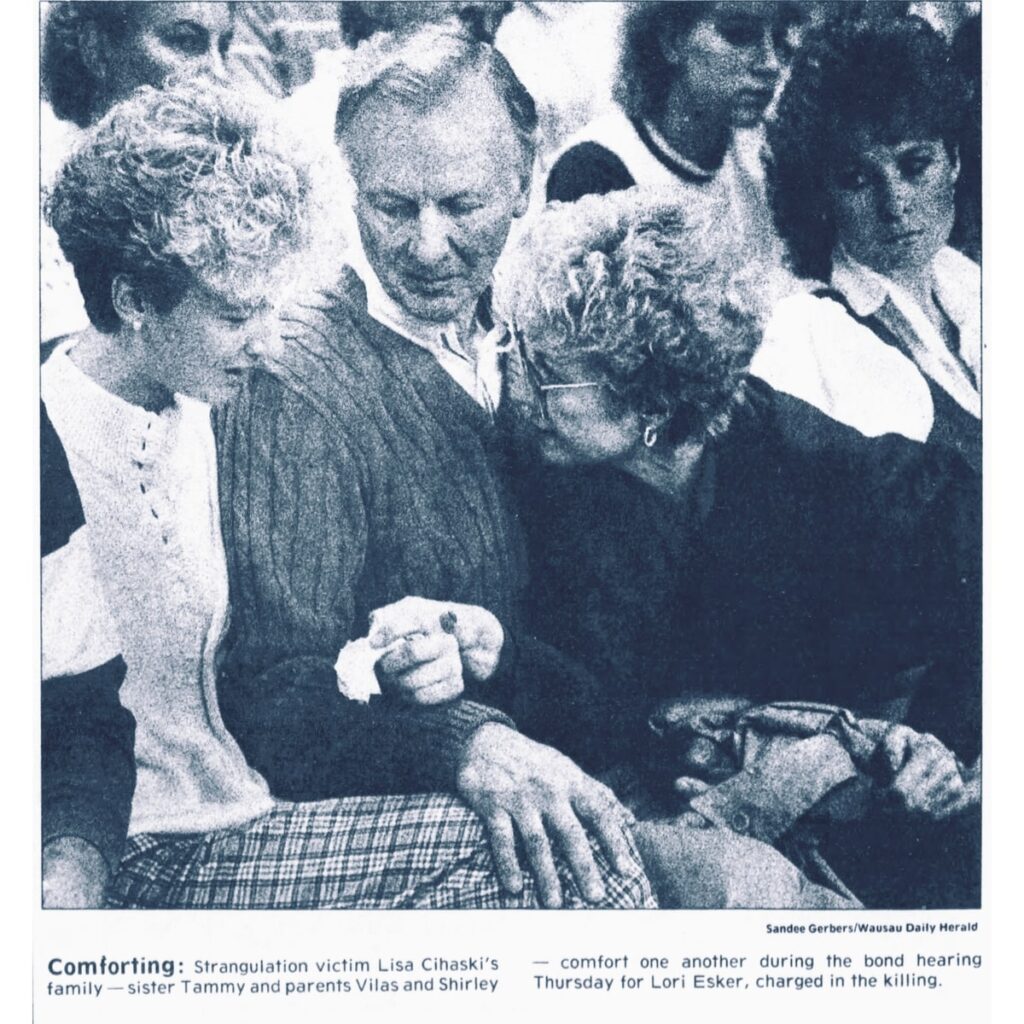

Born on Oct. 25, 1967, in Shawano County, Cihaski spent most of her life in Birnamwood in a spacious two-story blue house on Pine Road with her parents, Vilas and Shirley Cihaski, and sister, Tammy Cihaski.

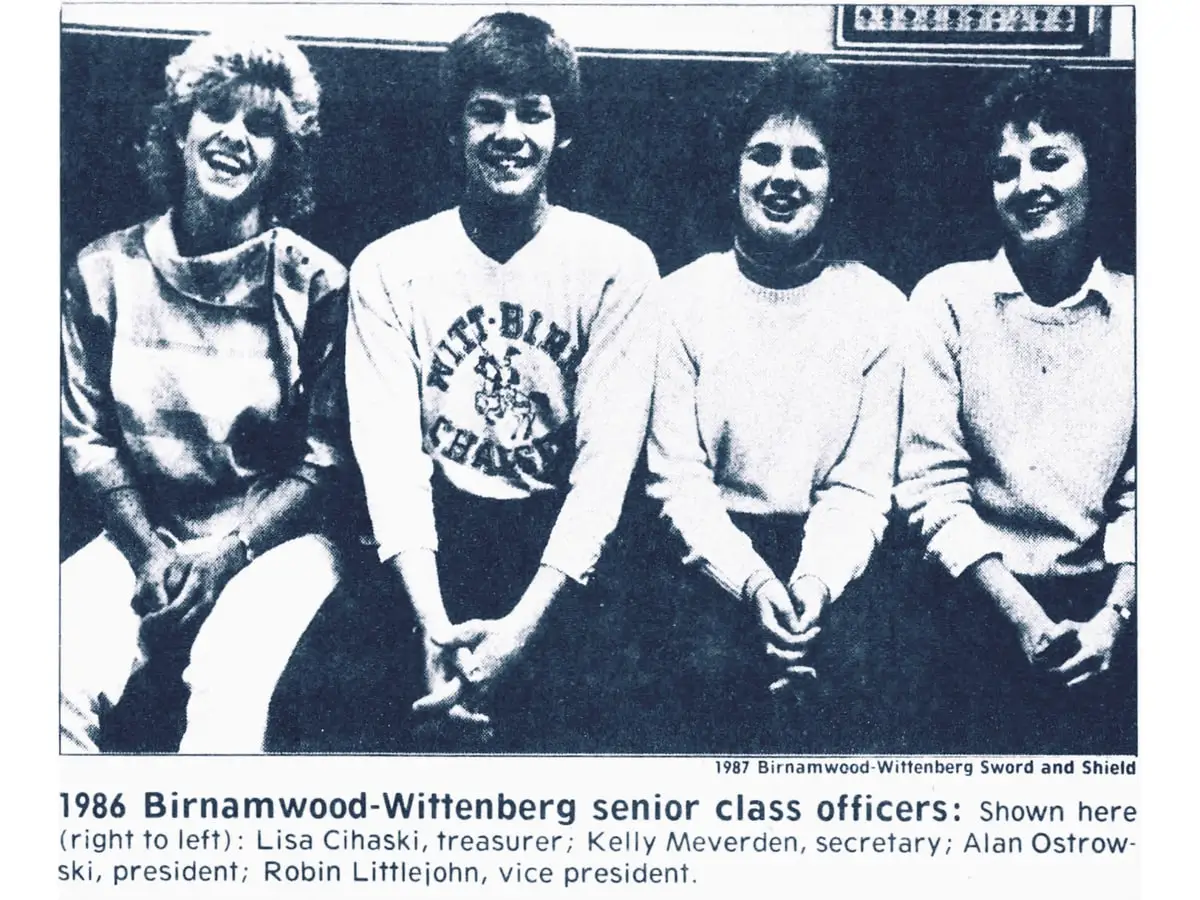

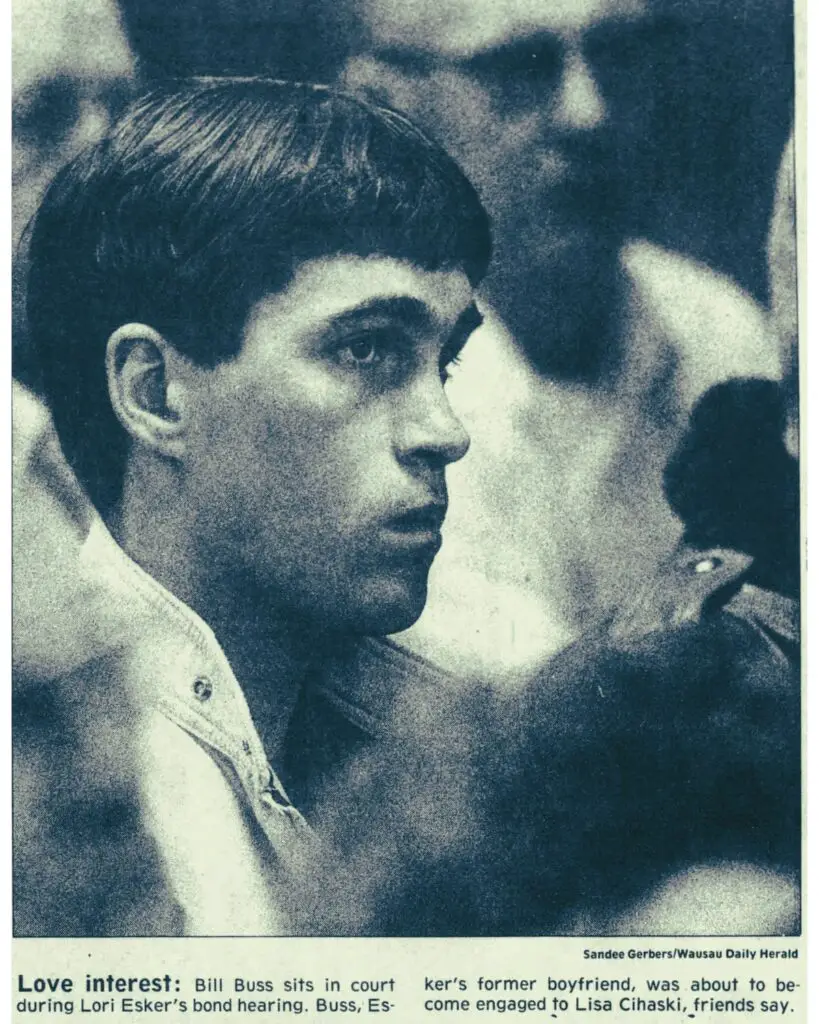

Cihaski graduated from Wittenberg-Birnamwood Senior High School in 1986. She dated Bill Buss, three years her senior, off and on for several years in high school and after.

Buss had graduated from the same school and came from a long line of dairy farmers; His grandparents, William and Mary Buss, homesteaded the Buss Farm in the late 1800s. Buss lived with his parents on the farm.

After high school, Cihaski spent five months studying travel planning at Dakota County Technical College in Rosemont, Minnesota, graduating with a 4.0 GPA.

Before leaving for college, Buss and Cihaski broke up. Cihaski returned to Birnamwood in January 1987 and worked as a front desk clerk at Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in Rib Mountain before being promoted to sales and catering assistant manager. She also worked occasional weekends at Chet and Emil’s, a popular Birnamwood bowling alley and restaurant.

Friends and family described Cihaski as a “sweet, caring and pleasant person” who dreamed of marrying and having children one day.

In June 1989, Buss and Cihaski realized how much they missed one another and continued their relationship.

During their breakup, Buss met and dated Lori Esker, then 20, for several months. He had met her through a mutual friend.

Esker was a junior at the University of Wisconsin, River Falls, majoring in agricultural journalism and communications. She had attended high school with Cihaski, graduating a year later.

That summer, Esker was crowned Marathon County Dairy Princess. According to reports, she was a sweet person and undoubtedly intelligent, having graduated high school as a national honor society member.

But the breakup with Buss devastated her, and she dramatically changed afterward. Her friends later said she became obsessed with him and hated Cihaski for coming between them.

On June 23, 1989, Buss and Esker attended a dance together. Cihaski and her close friend, Kelly Meverden, were also there. Esker later told investigators that she realized Buss had left the dance without her. She assumed he had gone home, so she drove to the Buss farm to help him with the midnight milking. However, when she arrived, Cihaski and Meverden were outside the barn. Esker was livid, and a shouting match between her and Cihaski ensued and cooled off shortly after.

A week later, Esker returned to the Buss farm unannounced to speak to Buss, but Cihaski was there. Another shouting match followed. Buss told Esker he no longer wanted a relationship with her and that he loved Cihaski.

On Sept. 16, 1989, Cihaski and Esker saw each other again at a wedding dance. Esker and her friend arrived between 8:30 and 9 p.m. Buss and Cihaski showed up as they left, but Esker claimed she ignored the couple.

Esker said it bothered her that she had not spoken to Buss and Cihaski at the dance, so at 1 a.m., she drove to the Buss farm. According to Esker, Cihaski was not there, so she left.

Esker called Cihaski’s workplace two days later to speak with her, but Cihaski was absent. Later, she called from a campus phone at one of her jobs but could not reach Cihaski.

Esker rented a car the following day to “get things straightened out” with Buss and Cihaski.

On Sept. 19, 1989, Esker’s class ended at 3:50 p.m. She rented a car from Wolfe Auto Center in River Falls and picked it up the following morning. Esker drove across the street to the Auto Stop gas and convenience store to purchase a bag of chips and a Mountain Dew for her two-and-a-half-hour drive to Wausau.

Cihaski was scheduled to work on Sept. 20, 1989, from noon to 8:30 p.m. She was dressed in a white, short-sleeved sweater with padded shoulders that belonged to her mother and a navy blue skirt with a back slit. She completed the ensemble with a thin blue belt, blue flats, gold stud earrings, and a ring.

Cihaski drove to work in her 1989 Oldsmobile Calais, purchased in August. She expected a busy night at the motel because of a banquet she helped organize. She had plans to meet Buss after work to watch him shoot darts, but her car’s oil light kept flickering. So, Cihaski canceled her plans with Buss and asked him to meet her at the Cihaski house after his match. Then she would go with him to do his midnight milking.

Cihaski turned down an invitation to have a drink with co-workers at the hotel bar. She walked out of the hotel at 8:45 p.m.

What happened next is solely based on Esker’s statement to the police.

When Cihaski exited the motel, Esker was there and asked if they could talk. Cihaski agreed. Before getting in her car, Cihaski removed her belt and placed it on the back seat.

The two women sat in Cihaski’s car, and an argument broke out at some point. Esker lied, said she was pregnant with Buss’ child, and accused Cihaski of cheating.

Esker claimed Cihaski attacked her first by grabbing her hair and throat. According to her, Cihaski became distracted by a guest walking out of the hotel, so Esker pushed her into the seat with her forearm across Cihaski’s throat. She noticed the belt in the backseat, grabbed it, and wrapped it tightly around Cihaski’s throat until Cihaski went limp.

Esker then dumped the contents of Cihaski’s purse, found a mirror, and held it up to her rival’s face to see if she was breathing, but Cihaski was dead. She then removed the ring from Cihaski’s finger, thinking Buss had given it to her. Esker initially told investigators that she picked the ring up off the floor but changed her story when they asked how it ended up on the floor.

After killing Cihaski, Esker drove to River Falls and returned the rental car the following day. An employee gave her a ride to the More-4 Store. There, Esker threw Cihaski’s ring into the trash. She attended classes that morning after tossing Cihaski’s belt in the dormitory incinerator.

Meanwhile, Cihaski’s parents became concerned when she had not come home all night.

Early in the morning on Sept. 21, 1989, Shirley Cihaski drove to the hotel and found her daughter dead in her car. She ran inside and told the front desk clerk to call the police.

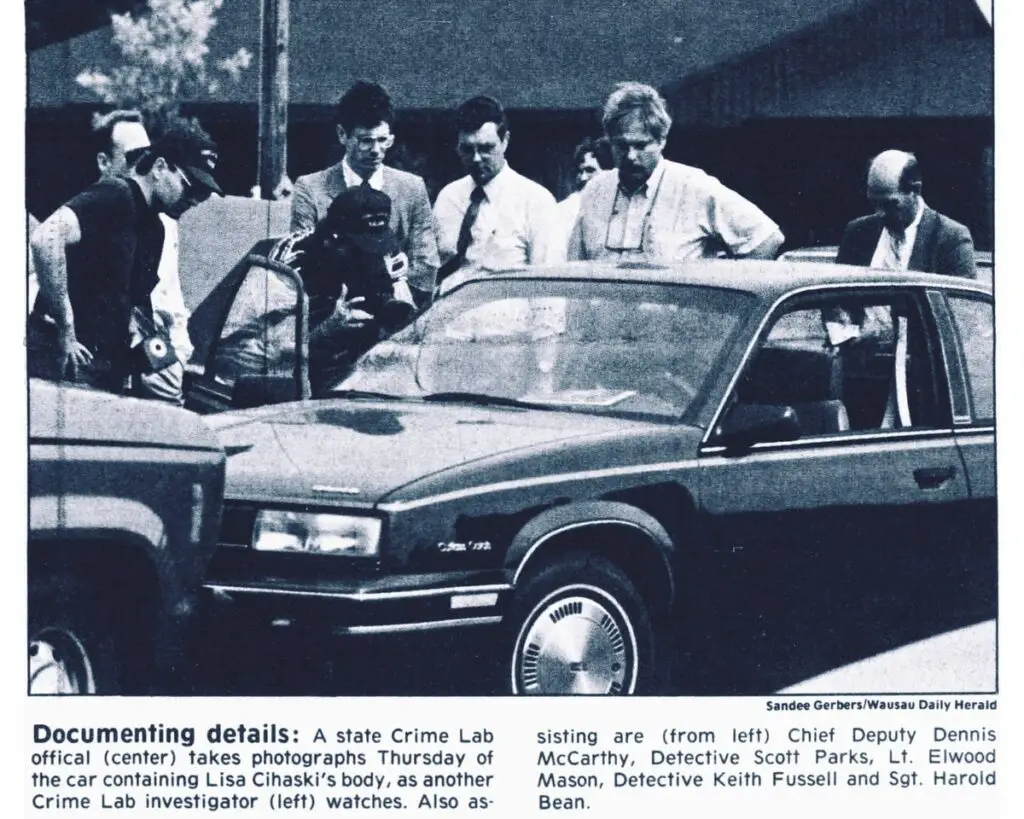

When Marathon County investigators and officials from the state Crime Lab in Madison arrived at the crime scene, they searched Cihaski’s car, collected several evidence items, and photographed and videotaped everything inside.

Madison pathologist Dr. Robert Huntingon III performed the autopsy and determined Cihaski had died from ligature strangulation and later said that her death took a minimum of two minutes. She received blunt-force injuries to her head, intestines, and lungs. The head wound was likely caused when Cihaski’s head was jammed between the seats into the floor hump of her car.

Huntington later testified in court that nothing in the car would explain the injuries to the intestines and lungs. “If the assailant threw a knee or a hip into her while holding her down, that would explain it,” he said. Fingernail markings on Cihaski’s neck were likely hers as she fought for her life.

Authorities asked Buss if he knew anyone who would harm Lisa, and he immediately named Esker.

Esker was one of 18 suspects interviewed by deputies in the nine days following Cihaski’s murder. She became the focus of the investigation after giving inconsistent statements to the police during her 90-minute interview on Sept. 24, 1989, in River Falls.

On Sept. 29, 1989, authorities interviewed Esker again at the sheriff’s department and asked her to provide hair and fingerprint samples; Esker agreed. At 7:45 p.m., she was advised of her rights, waived her right to a lawyer, and confessed to the killing. Police asked her to re-enact the killing, with a deputy portraying Cihaski.

Following Lori’s direction, Sgt. Randall Hoenisch first grabbed her arm, shook it, and then let go. Then he put his hand to her throat; Lori placed her left forearm against Hoenisch’s throat. Hoenisch said Lori was “not at all shy or hesitant how she did this.” Instead, she was “aggressive & applied a great deal of pressure to my throat with her forearm. As a matter of fact, she had me off my chair and up against the wall in the interview room,” Hoenisch wrote in his report. Lori then took his belt and “in a split second, had it wrapped around my neck and once again, applied a good amount of pressure to my neck, this time using the belt,” he continued.

Wausau Daily Herald, Oct. 8, 1989

Esker appeared at an arraignment hearing in Marathon County Circuit Court on Monday, Oct. 2, 1989. She was charged with first-degree intentional homicide and held without bail. Approximately 60 friends and relatives of Cihaski and Esker packed the courtroom.

At a bond hearing three days later, Marathon County Circuit Court Judge Michael Hoover released Esker on a $100,000 bond, ordering her to stay with her parents and away from key witnesses such as Buss and Meverden.

Esker was the first woman charged with slaying another woman in Marathon County. Cihaski’s murder made national news.

The trial took place over one week in June 1990, with Judge Hoover presiding. District Attorney Greg Grau represented the prosecution, and attorney Stephen Glynn defended Esker.

The jury was selected from Florence County because of pre-trial publicity.

The prosecution presented to the jury that Esker was obsessed with Buss and eliminated her rival out of jealousy. Glynn countered, saying Esker did not intentionally kill Cihaski; Her death was a tragic accident. Grau argued that Esker showed intent when she grabbed the belt.

At one point in the trial, Grau silenced the courtroom for two minutes to show how long it took for Cihaski to die and that at any moment, Esker could have stopped and released the belt around Cihaski’s neck, but she did not. Several witnesses testified throughout the trial, including Buss and Tammy Cihaski. Esker did not testify on her behalf.

The jury deliberated for seven and a half hours on June 15, 1990. Judge Hoover advised before deliberations; the jury could go beyond first-degree intentional homicide — such as second-degree intentional homicide, which considers provocation and self-defense and carries a maximum sentence of 20 years in prison. However, the jury found Esker guilty of first-degree intentional homicide, and Hoover later sentenced her to life in prison with the possibility of parole in 2004.

Glynn said he would appeal the conviction. At a post-conviction hearing in October 1991 for a retrial bid, Esker’s attorneys said the jury instructions confused the jury in the 1990 trial, but Judge Hoover denied the motion.

Hoover: “I can’t find, I can’t conclude, I can’t believe, that this jury was ultimately confused in (applying) the instructions. These are not people who live in a vacuum until they walk into the jury room. They know what the issues are.”

Esker was absent at the hearing. Her lawyers appealed again. But in May 1992, the 3rd District Court of Appeals upheld her conviction. The Leader-Telegram reported, “In her appeal for a new trial, Lori Esker alleged two of her confessions were involuntary and inadmissible ‘because the authorities used fundamentally unfair and psychologically coercive tactics and strategies,’ according to appellate court records. She again argued her due process rights were violated because the jury instructions were confusing and misleading.”

The court concluded that Esker’s confessions were “voluntary, and the jury instructions were not reasonably likely to confuse or mislead the jury.” The court also ruled that “tactics were not fundamentally unfair or so coercive as to exceed Esker’s will.”

Cihaski’s family filed a wrongful death suit against Esker so she would not profit from the killing. Esker and her legal team had received book, film, and television offers and paid interview requests from journalists. Judge Michael Hoover signed the wrongful death judgment in an out-of-court settlement in early August 1992, which allowed Cihaski’s family access to Esker’s assets, and ordered Esker to pay $350,000 to the Cihaski family.

According to the Wausau Daily Herald, “A 1970s Wisconsin law — dubbed the Son of Sam law — prevents someone convicted of first-degree intentional homicide from profiting from the crime.” Instead, any money Esker could have earned would be paid to a state-run trust fund. The law was named after serial killer David Berkowitz, aka Son of Sam, who had profited from book and movie deals.

In 1995, an NBC Movie called “Beauty’s Revenge,” starring “Melrose Place” star Courtney Thorne-Smith and “Growing Pains” actress Tracey Gold, was loosely based on Cihaski’s killing.

Wausau developer Ghidorzi Cos demolished the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge a few years ago to make room for the Hilton Garden Inn hotel. You can click here to see pictures of the motel.

In July 2019, nearly 30 years after killing Cihaski, Esker was released from prison. Her whereabouts are unknown, but she likely returned to the Esker farm in Hatley. Esker has never shown any remorse for killing Cihaski, and her parents sat stone-faced in the courtroom throughout her trial.

Buss found love again and married Linda Gritzmacher in May 1993. They have two sons. However, the couple divorced in recent years. Buss still lives in the Eland area.

Tammy Cihaski married David Fischer in 1994, and they reside in the Birnamwood area, as does Shirley Cihaski. Vilas Cihaski died in 2016.