Born in Chicago to Emanuel and Patria Rothschild on Nov. 14, 1949, Christine Rothschild was one of seven children and the second oldest daughter. Two children were stillborn, and her one-year-old brother, Richard, died in 1942.

The Rothschilds resided in a two-story English Tudor home at 6338 North Kenmore Avenue in Chicago’s Edgewater lakefront community.

Christine graduated from Nicholas Senn High School in 1967, placing fourth out of 500 students. She had plans to attend Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, to study journalism. However, her mother insisted Christine attend either the University of Wisconsin-Madison or Chicago’s Loyola University.

Christine decided on UW-Madison but still dreamed of attending Vassar. In the fall of 1967, she moved into room 119 of Ann Emery Hall at 265 Langdon Street.

Christine settled in quickly and established a daily routine. She would walk on campus every morning at 7 a.m., and stop outside University Hospital to smoke with medical residents and staff. She would end her route at Rennebohm Drug Store, either its State Street or University Drive location.

During one of these cigarette breaks, medical school resident Niels Jorgensen, 42, spotted Christine for the first time.

Jorgensen liked young college girls, specifically tall, blonde, and affluent. He introduced himself when he saw Christine smoking at the hospital during the second week of April 1968.

When he learned Christine’s surname was Rothchild, he mistook her as related to the notable European Rothschild family.

Jorgensen was from California and stood over 6 feet tall. He had sandy blonde hair, blue eyes, an athletic physique, and a mustache. But Christine immediately disliked him and tried to steer clear of him. She thought he was strange and cold to his peers. His attraction to Christine evolved into a full-blown obsession, similar to that of Glenn Close’s character in the 1987 film “Fatal Attraction.”

Christine soon received prank phone calls from a silent caller. One day she saw a man standing outside her dorm window watching her.

Jorgensen once followed Christine to Memorial Library, where she regularly studied, and asked her on a date, but she declined.

The phone calls went from silent to threatening. She never told anyone what the caller said other than the calls were terrifying. The stalking also escalated; everywhere Christine looked, she saw Jorgensen.

Jorgensen’s harassment dramatically affected Christine, and her demeanor changed. She rarely smiled and became anxious.

In early May 1968, Christine returned to Chicago to speak with her mother about transferring to Vassar College. The deadline for fall registration was approaching, and she desperately wanted to leave Madison.

Christine spent the weekend trying to convince her mother about Vassar, but her mother refused, which highly upset Christine. While leaving her family’s home to return to Madison, Christine sobbed and repeatedly told her mother that she hated her. The emotional confrontation would haunt Patria Rothschild for the rest of her life.

However, Christine’s parents relented two days later. They planned to surprise her at the end of the school year with a celebration. Unfortunately, tragedy would strike first.

After Christine returned to UW, she spotted campus police officers Tiny Frey and Roger Golemb standing near the top of Bascom Hill. She decided to report Jorgensen’s harassment. They seemed unconcerned. Frey told her to buy a whistle instead, which she already had as a Christmas gift from her mother.

Golemb checked reports the following day, but Christine’s complaint was not listed, and he never asked Frey about it.

Sunday, May 26, 1968, was rainy and gloomy, a fitting scene for what would happen next.

At 3 p.m. that day, a boy riding in a car with his family on North Charter Street hollered at his parents. He said that he saw someone lying in the bushes outside Sterling Hall. They ignored him, thinking it was a college prank involving a mannequin.

About an hour later, Philip Van Valkenberg, 23, passed Sterling Hall as he walked toward a friend’s office. He saw lights on in Sterling Hall’s machine shop and thought his friend was there doing work, as he often did. Typically, Philip would have walked through Sterling’s main doors and down to the basement where his friend was working.

The main doors were locked. He leaned over the right front railing to knock on a lower-level window alerting his friend to unlock them.

Philip glanced down at the bushes and saw a female’s lifeless, battered, and bloody body lying on the ground. He immediately called the police.

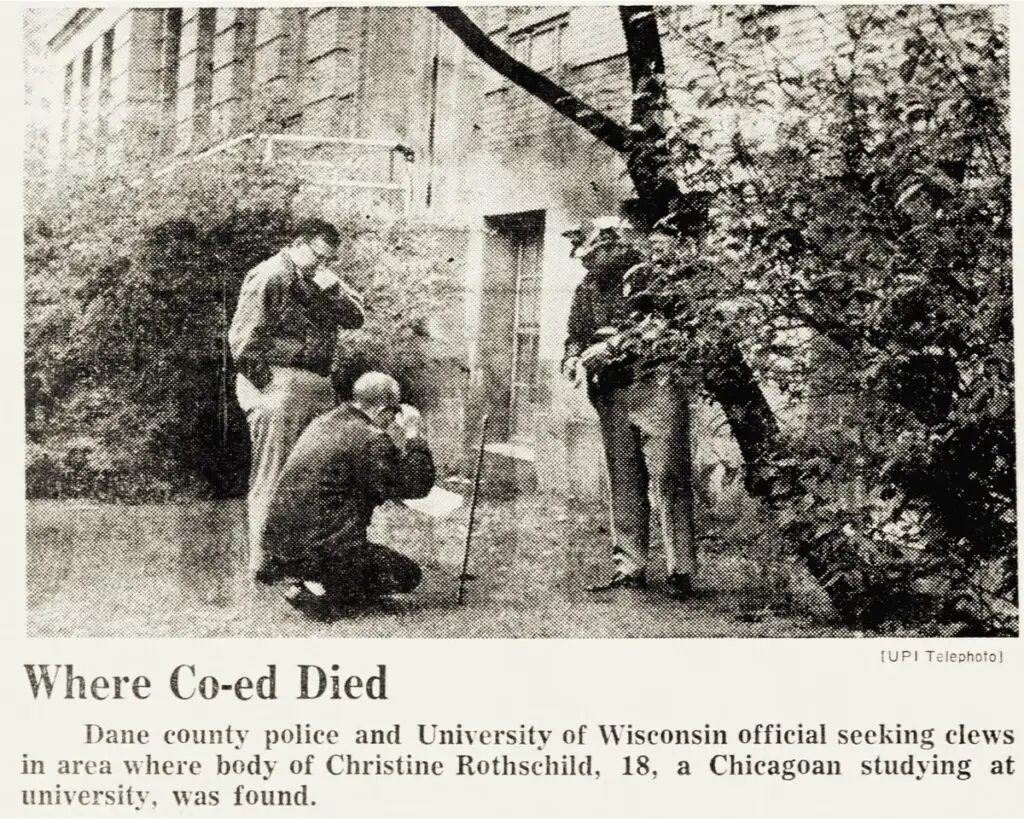

Police arrived and secured the crime scene. They bagged several items of evidence, took photographs of the victim’s body, and searched the area for the murder weapon.

The victim wore a beige coat, a blue cotton mini-shift dress, and boots and carried no purse. A piece of cloth from the lining of her jacket was twisted tightly around her throat. Police removed it at the crime scene.

Investigators found a plastic cigarette case and dorm room key alongside the body. The victim’s broken and open umbrella was nearby.

Officers quickly ruled out robbery as a motive because the victim wore two expensive rings on her fingers.

One of the officers at the crime scene was Officer Golemb. He recognized the body as soon as he saw it as the woman who filed the harassment claim. However, he could not remember her name. Later, Golemb and Frey kept quiet about Christine’s harassment complaint against Jorgensen for fear of losing their jobs.

Authorities transported the body to St. Mary’s Hospital. A nurse identified Christine by the name sewn into the neckline of her shift.

Dr. Clyde “Bud” Chamberlain, St. Mary’s chief pathologist and Dane County coroner since 1961, performed the autopsy. He determined Christine had been stabbed with a surgical scalpel 14 times in the breast, chest, and neck. But a single stab to the heart killed her.

Chamberlain discovered both of Christine’s gloves lodged deep inside her throat. Her jaw was broken, likely from a fist blow to the face. She also had several fractured ribs. There was no evidence of a sexual assault.

Stomach contents revealed Christine had consumed a spinach salad an hour before her murder. Chamberlain estimated the crime to have occurred around 7 a.m.

On May 29, 1968, authorities sent stained pants found near the Rothschild crime scene and other evidence to the FBI Crime Lab in Washington for analysis. However, experts found nothing conclusive. Blood on Christine’s clothing and a blood-soaked man’s handkerchief belonged to Christine.

UW Police Department led the Rothschild murder investigation, assisted by Madison Police Department, Dane County Sheriff’s Office, and the FBI. Investigators created a six-team task force of UWPD officers and four detectives from the other agencies.

Gertrude “Trudy” Armstrong was the night hostess at Ann Emery Hall. She told investigators she saw Christine at 4 a.m. walking to the bathroom wearing her blue nightgown.

Early news reports stated another resident thought she saw Christine around 10 a.m. exiting a side door in the dorm. Christine was wearing a beige raincoat, a beige umbrella, and a ribbon in her hair.

Chief Hanson believed that someone working the morning shift at the hospital on the day of the murder must have seen something because the hospital was near the crime scene. Yet, no hospital employees ever came forward, and police did not interview them within the first 48 hours.

Over the next two years, police conducted 1,500 interviews without results.

The day after Christine’s murder, Jorgensen was fired from his medical residency. He briefly lived in Dearborn, Michigan, Philadelphia, and New York City. Madison detectives flew to New York City to interview Jorgensen. However, when they arrived at his apartment, he said he was ill and asked if they could do it another time. For whatever reason, the officers agreed. When they returned later, he had fled.

Jorgensen moved back to California, where he lived with his mother, Harriet Jorgensen. His father, Niels Jorgensen, Sr., died in 1974.

On Sept. 6, 1949, Jorgensen’s younger brother Robin Claude Soren Jorgensen, 20, drowned in 50 feet of water in Little Harbor on Catalina Island’s west side after his air compressor failed. Soren’s line tender, James Reid Luntzel, Jr., also 20, attempted to rescue Soren but failed. The family later learned that Soren’s “40-pound diving belt had become fouled and he was unable to loosen it,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

Soren was a professional abalone diver, and Jorgensen was an experienced diver. The two usually went fishing together. However, on the day of Soren’s death, Jorgensen did not go. Harriet always believed Jorgensen killed Soren by cutting Soren’s diving hose before the fishing trip. Harriet died in 1984.

Linda Tomaszewski Schulko first met Christine during UW’s orientation week in 1967. The two became friends after realizing they had several things in common.

On Wednesday, May 22, 1968, Christine and Linda met up on Bascom Hill. Linda asked her to attend the Saturday night swim meet; Christine said yes. Linda said she would call her on Friday night. Instead, Linda decided to go home to Milwaukee for the weekend to work on a term paper at the last minute. She called Christine early Friday morning, but there was no answer. Linda assumed Christine was on her morning walk.

At 2:15 a.m. on May 27, 1968, Linda received a call from Officer Hendrickson of the UW Campus Police asking when she last saw Christine. She told him she last saw her friend on May 22. Hendrickson said nothing more than a quick thank you before hanging up. Later that morning, her father watched the news as the broadcaster announced Christine’s murder.

Following Christine’s killing, the case went cold. Because Frey and Golemb kept quiet about the harassment claim against Jorgensen, investigators never had him on their radar as a suspect.

But Linda believed Jorgensen had killed Christine because she had told Linda about his harassment and stalking. Linda began her own investigation and made it her life’s mission to get justice for her friend.

She spent decades going back and forth with UW and Madison police. She interviewed former UW students and hospital medical staff and even tracked down and confronted Jorgensen. During a phone conversation, Linda mentioned something about the “good dying young.” Jorgensen immediately fired back, “Ms. Rothschild died because she deserved it,” and that he alone had “the scoop on her.”

More than four decades after the murder, Madison police announced a person of interest in Christine’s case in August 2009. William Floyd Zamastil, 57, was serving a life sentence for the 1978 rape and murder of a Madison woman. At the time of the announcement, he had been indicted in Arizona for a 1973 rape and murder. Zamastil was 16 in 1968.

Linda was skeptical. Christine would have been Zamastil’s first victim. Linda questioned whether he would have had the “confidence and experience to commit such a personal and complex crime,” she wrote in her book Murder on the 56th Day. Furthermore, Zamastil sexually assaulted and shot his victims then dumped their bodies away from the crime scene.

In 2011, criminologist Michael Arntfield of Western University, London, Ontario, assigned his class a project: the Rothschild murder.

One of his students contacted Linda and asked if she would be willing to share her research on Christine’s death. Linda agreed and gave them Jorgensen’s telephone number in case the student wanted to interview him. The student spent 90 minutes interviewing Jorgensen. He denied knowing Christine and spent most of the time rambling or giving his hypothesis of the murder.

Western News reporter Jason Winders writes, “A polygraph examiner and trained statement analyst analyzed the recording and transcript, and confirmed Arntfield’s professional opinion and suspicions about the suspect.”

Arntfield wrote “Mad City: The True Story of the Campus Murders That America Forgot” in 2017, which includes Christine’s murder.

Jorgensen would evade an arrest; he died on Feb. 16, 2013, at 87.

I highly recommend reading Linda’s book as it goes into great detail regarding the life of Christine, her killing, and Linda’s hunt for justice. It is an excellent read and the primary source for this article.

Other sources: Chicago Tribune; Wisconsin State Journal; University of Wisconsin-Madison.